How to Pasteurize Substrate to Prevent Contamination sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail with formal and friendly language style and brimming with originality from the outset.

Understanding and implementing effective substrate pasteurization is a cornerstone for successful cultivation, whether you’re nurturing mushrooms or growing plants. This comprehensive guide delves into the critical importance of this process, exploring the biological threats posed by contaminants and the distinct difference between pasteurization and sterilization. By mastering these techniques, you’ll significantly enhance the viability of your growing mediums and pave the way for healthier, more abundant yields.

Understanding Substrate Pasteurization

Pasteurizing your growing substrate is a critical step in cultivating healthy mushrooms or plants, as it significantly reduces the risk of encountering detrimental organisms. This process is designed to eliminate or drastically reduce the populations of harmful microorganisms while preserving beneficial ones, creating an optimal environment for your desired species to thrive. By carefully controlling temperature and time, we can effectively prepare our growing medium.The fundamental purpose of pasteurizing a substrate is to create a clean slate for your cultivation efforts.

It’s about giving your chosen fungi or plants the best possible start by removing competitors and pathogens that could otherwise hinder their growth, outcompete them for nutrients, or even cause disease. A well-pasteurized substrate minimizes these threats, allowing your crop to flourish.

Biological Rationale for Contamination Control

Contamination poses a significant threat to substrate viability because it introduces organisms that compete directly with your intended crop for essential resources such as nutrients, water, and oxygen. These competing organisms, often bacteria, molds, or other fungi, can grow much faster than your desired species, quickly overwhelming the substrate and preventing your crop from establishing or maturing. Furthermore, some contaminants produce toxins that can be lethal to your cultivation.

Common Contaminants in Growing Mediums

Various contaminants can affect different growing mediums, each with its own preferred conditions and impact. Understanding these common culprits helps in recognizing potential issues early on.Here are some prevalent types of contaminants:

- Trichoderma (Green Mold): A common and aggressive mold that thrives on many mushroom substrates, turning green as it sporulates. It rapidly colonizes the substrate, consuming nutrients and releasing enzymes that can break down the mycelium of cultivated mushrooms.

- Bacillus Species (Bacterial Blotch): Various bacteria, often appearing as slimy or watery patches on the substrate surface, can cause “bacterial blotch” or soft rot. These bacteria compete for nutrients and can produce foul odors.

- Penicillium (Blue/Gray Mold): Similar to Trichoderma, Penicillium species are molds that can appear as fuzzy blue or gray colonies. They are also aggressive competitors and can damage mycelium.

- Cobweb Mold (Dactylium): This mold appears as a wispy, cobweb-like growth that can quickly cover the substrate. While not always directly lethal, it indicates suboptimal environmental conditions and can outcompete the desired mycelium.

- Rhizopus (Bread Mold): Often seen as a fast-growing, white, cottony mold, Rhizopus can rapidly colonize substrates, particularly those with high moisture content.

Distinguishing Pasteurization from Sterilization

While both pasteurization and sterilization aim to reduce microbial load, they differ significantly in their approach and the resulting microbial environment. This distinction is crucial when preparing substrates for cultivation.Sterilization involves heating a substrate to a temperature high enough to kill all living organisms, including spores, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. This is typically achieved through methods like autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for a specific duration.

Sterilization creates a completely sterile environment, meaning no life exists within the substrate. This is often employed for laboratory cultures or very sensitive applications where even the slightest contamination is unacceptable.

Sterilization eliminates all microbial life.

Pasteurization, on the other hand, involves heating a substrate to a lower temperature for a shorter duration than sterilization. The goal of pasteurization is not to kill all microorganisms but to reduce the population of pathogenic and competing organisms to levels that are not detrimental to the desired crop. Crucially, pasteurization aims to leave behind some beneficial microorganisms, such as certain bacteria and thermophilic fungi, which can help in suppressing the growth of more aggressive contaminants.

Common pasteurization temperatures range from 60°C to 80°C (140°F to 176°F), depending on the specific method and substrate.

Pasteurization reduces harmful microbes while preserving beneficial ones.

The key difference lies in the outcome: sterilization results in a completely inert medium, whereas pasteurization yields a medium with a reduced population of undesirable microbes and a preserved community of beneficial ones. For many mushroom and plant cultivation applications, pasteurization is preferred because the presence of beneficial microbes can provide a degree of natural resistance against subsequent contamination.

Key Principles of Pasteurization

Pasteurization is a cornerstone technique in preventing microbial contamination of substrates, particularly in biological applications like mushroom cultivation. Its effectiveness hinges on precisely controlled heat application to reduce the population of pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms to a level that is unlikely to cause disease or spoilage. This process targets specific types of microbes and their susceptibility to heat, aiming to eliminate the most detrimental ones without significantly altering the substrate’s nutritional value or structure, which is crucial for the desired biological growth.The scientific basis of pasteurization lies in the thermal denaturation of essential cellular components within microorganisms.

Heat disrupts the three-dimensional structure of proteins, including enzymes vital for metabolic processes, and damages nucleic acids like DNA and RNA. This damage incapacitates the microorganisms, preventing them from replicating and causing spoilage or disease. The effectiveness is directly related to the intensity of heat (temperature) and the duration of exposure (time).

Thermal Inactivation of Microorganisms

The core principle of pasteurization is to reach temperatures high enough to kill or inactivate vegetative microbial cells and some spores, while minimizing damage to the substrate itself. Different microorganisms have varying heat resistances, with vegetative cells generally being more susceptible than bacterial spores. The goal is to create a thermal death curve where the probability of a viable microorganism surviving is extremely low.

“Heat acts by denaturing essential cellular proteins and enzymes, leading to irreversible damage and cell death.”

Temperature and Time Parameters

The specific temperature and time required for effective pasteurization depend on the target microorganisms and the substrate’s composition. For most common contaminants in organic substrates, temperatures between 60°C (140°F) and 80°C (176°F) are generally sufficient when applied for a sustained period. A common benchmark is holding the substrate at 70°C (158°F) for 30 minutes. However, longer holding times at lower temperatures or shorter times at higher temperatures can achieve similar results, following established thermal death time curves.

For instance, a lower temperature like 63°C (145°F) might require a longer holding time of 30 minutes, whereas a higher temperature like 77°C (170°F) might only need a few minutes. It’s crucial to understand that while higher temperatures kill microbes faster, they also increase the risk of substrate degradation.

Role of Moisture Content

Moisture content is a critical factor in the efficacy of pasteurization. Water acts as a heat transfer medium, facilitating the penetration of heat throughout the substrate. Microorganisms are most vulnerable to heat when their cellular structures are hydrated. A substrate that is too dry will not heat effectively, leaving pockets of viable microbes. Conversely, a substrate that is too wet can lead to anaerobic conditions during heating, promoting the growth of undesirable thermophilic (heat-loving) bacteria that can survive pasteurization temperatures and outcompete beneficial organisms later.

An ideal moisture content for most substrates is typically between 50% and 70%, often described as the point where a handful of the substrate can be squeezed, yielding a few drops of water, but not a stream.

Achieving Necessary Thermal Conditions

Various methods are employed to achieve the required thermal conditions for pasteurization, each with its advantages and limitations. The choice of method often depends on the scale of operation, available resources, and the specific substrate.

- Hot Water Bath: This is a common method for smaller batches. The substrate is sealed in a heat-resistant container (like a food-grade bucket or bag) and submerged in a water bath maintained at the target temperature for the specified duration. This method ensures even heating due to water’s excellent heat transfer properties.

- Steam Pasteurization: This method utilizes steam, which can heat the substrate more rapidly and at higher temperatures than hot water. It can be achieved by direct steaming of the substrate in a sealed container or by using a steam-jacketed vessel. Steam pasteurization is highly effective but requires careful monitoring to prevent overheating and excessive moisture absorption.

- Pressure Cooking (Autoclaving): While often associated with sterilization, pressure cooking at specific temperatures and times can also serve as a form of pasteurization. Autoclaves use pressurized steam to reach temperatures significantly above boiling point (e.g., 121°C or 250°F), but by adjusting the time, one can achieve pasteurization-level reduction of microbial load without complete sterilization. This is a very effective method for heat-tolerant substrates.

- Oven Pasteurization: This method involves heating the substrate in an oven. While convenient, achieving uniform temperature throughout a dense substrate can be challenging, often leading to uneven pasteurization. It’s generally less preferred for critical applications due to potential for temperature gradients.

Each of these methods relies on the principle of transferring sufficient heat energy to the substrate to denature microbial proteins and damage cellular structures. The key is to ensure that the core temperature of the substrate reaches and is maintained at the pasteurization threshold for the required time, while also managing moisture levels to prevent undesirable outcomes.

Common Pasteurization Methods

Once we understand the fundamental principles of substrate pasteurization, the next crucial step is to explore the various practical methods available. Each method offers a unique balance of effectiveness, scalability, and resource requirements, making it suitable for different scenarios, from hobbyist cultivation to larger-scale operations. Choosing the right method is key to successfully preventing contamination and ensuring a healthy substrate for your mycelial growth.This section will delve into several widely used techniques, providing detailed explanations and practical guidance to help you select and implement the most appropriate approach for your needs.

We will cover both heat-based and cold pasteurization options, examining their strengths and weaknesses.

Hot Water Bath Pasteurization

The hot water bath method is a popular and accessible technique for pasteurizing small to medium batches of substrate. It relies on maintaining a specific temperature for a set duration to eliminate most competing organisms while preserving beneficial ones. This method is often favored for its simplicity and relatively low cost, making it ideal for home growers.The process involves submerging the substrate, typically enclosed in a heat-resistant bag or container, in a large pot of water maintained at the target temperature.

Careful monitoring of the water temperature is essential to ensure consistent and effective pasteurization.

Oven Baking Pasteurization

Oven baking offers another accessible heat-based approach to substrate pasteurization, particularly suitable for smaller quantities. This method utilizes the dry heat of an oven to achieve pasteurization.The substrate is usually placed in a heat-resistant container or wrapped in foil to prevent direct contact with the oven elements and to trap moisture. The oven temperature and duration are critical parameters that need to be carefully controlled.

For oven baking, a common guideline is to bake the substrate at a temperature of 160-180°F (71-82°C) for approximately 90 minutes to 2 hours.

It is important to note that oven baking can sometimes lead to excessive drying of the substrate if not managed properly. Therefore, monitoring moisture content before and after the process is advisable.

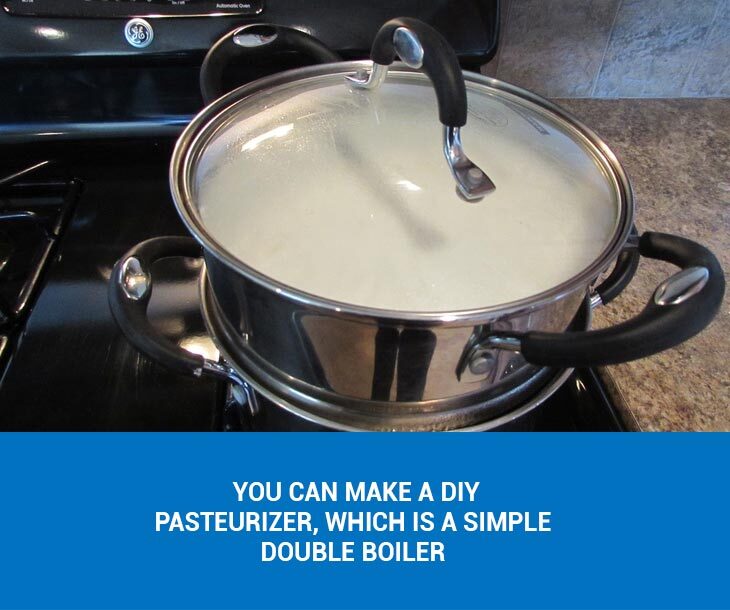

Steam Pasteurization

Steam pasteurization is a highly effective method for treating larger batches of substrate and is often favored in commercial settings due to its efficiency and ability to penetrate the substrate thoroughly. This technique uses the heat from steam to raise the substrate’s temperature.The primary advantage of steam pasteurization is its ability to reach and maintain target temperatures quickly and evenly throughout the substrate, effectively eliminating a broad spectrum of contaminants.

However, it typically requires more specialized equipment and a controlled environment compared to simpler methods. A potential disadvantage is the need for careful ventilation to manage the generated steam safely.

Comparison of Cold and Heat-Based Pasteurization Techniques

When considering pasteurization, a fundamental distinction lies between cold and heat-based methods. Heat-based techniques, such as hot water baths, oven baking, and steam pasteurization, work by denaturing proteins and damaging the cellular structures of microorganisms, effectively killing them. These methods are generally considered more potent in eliminating a wider range of contaminants.Cold pasteurization, on the other hand, aims to inhibit the growth of undesirable organisms without necessarily killing them.

Techniques might include using chemical agents or controlled atmospheric conditions. While cold pasteurization can be useful in specific applications, it is generally less effective at eradicating all competing microorganisms compared to heat-based methods. For substrate cultivation, where a sterile or near-sterile environment is paramount, heat-based methods are typically preferred for their more comprehensive decontamination capabilities.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Bucket Tek (Hot Water Pasteurization)

The “Bucket Tek” is a popular and straightforward method for hot water pasteurizing substrate, especially for hobbyists. It’s designed for ease of use and can be performed with common household items.Here is a step-by-step guide:

- Prepare the Substrate: Mix your chosen substrate components (e.g., coco coir, vermiculite, gypsum) in the desired ratios. Hydrate the substrate to field capacity, meaning it’s moist but not waterlogged. You should be able to squeeze a few drops of water from a handful when firmly compressed.

- Fill the Bucket: Pack the hydrated substrate loosely into a clean, food-grade bucket. Do not compact it too tightly, as this can hinder heat penetration.

- Add Water: Fill the bucket with clean water until the substrate is completely submerged. Ensure there is enough water to allow for expansion and to maintain the target temperature.

- Heat the Water: Place the bucket in a larger pot or container, or use a heat source that can maintain the water temperature around the bucket. A large stockpot with a heat source like a stove burner or a dedicated heating element can be used. The goal is to heat the water surrounding the substrate to the pasteurization temperature.

- Maintain Temperature: Heat the water to approximately 160-180°F (71-82°C). Use a thermometer to monitor the water temperature closely.

- Pasteurize: Once the target temperature is reached, maintain it for a minimum of 90 minutes to 2 hours. This duration is crucial for effectively pasteurizing the substrate.

- Cool Down: After the pasteurization period, allow the substrate to cool down naturally within the bucket. This can take several hours. Do not rush this process.

- Drain and Prepare: Once cooled to room temperature, carefully drain any excess water from the bucket. The substrate is now pasteurized and ready for inoculation.

Basic Setup for Steam Pasteurization

Steam pasteurization can be effectively implemented with a basic setup using readily available materials, making it accessible even for those looking to scale up slightly beyond the bucket tek.A common setup involves using a large stockpot with a lid, a way to elevate the substrate above the water, and a heat source.Here’s how to design a basic steam pasteurization setup:

- Container: A large, sturdy stockpot or a food-grade plastic bin with a tight-fitting lid is essential. The container should be large enough to hold your substrate and allow for steam circulation.

- Substrate Holder: To keep the substrate from direct contact with the water, you can use a perforated tray, a colander, or even bricks placed at the bottom of the pot to elevate a perforated container holding the substrate. Ensure there’s ample space between the water level and the substrate.

- Water Reservoir: A few inches of water are added to the bottom of the stockpot. This water will be heated to create steam.

- Heat Source: A stove burner, an outdoor propane burner, or any controllable heat source capable of bringing the water to a boil and maintaining a steady steam output is required.

- Lid and Sealing: A tight-fitting lid is crucial to trap the steam. For plastic bins, you might need to use foil or tape to ensure a good seal.

The process involves heating the water to a boil, allowing it to generate steam. The steam rises and envelops the substrate, raising its temperature to the pasteurization point (typically 160-180°F or 71-82°C). The substrate is then held at this temperature for a specified duration, usually 90 minutes to 2 hours, before being allowed to cool. Careful monitoring of the internal substrate temperature with a thermometer is recommended to ensure efficacy.

Substrate-Specific Pasteurization Considerations

While the core principles of pasteurization remain consistent, the ideal approach can vary significantly depending on the composition of your substrate. Different materials have varying levels of natural microbial load, nutrient content, and physical structures, all of which influence how effectively and safely they can be pasteurized. Understanding these nuances is crucial for minimizing contamination and promoting successful mushroom cultivation.The type of substrate directly impacts the required temperature, duration, and even the method of pasteurization.

For instance, a dense, nutrient-rich substrate like straw requires a different treatment than a more inert material like coco coir. Tailoring your pasteurization strategy to the specific substrate ensures that you effectively reduce competitor organisms without degrading the substrate’s beneficial properties or cooking it to the point where it becomes unsuitable for mycelial colonization.

Optimal Pasteurization Parameters for Common Substrates

Different mushroom cultivation substrates possess unique characteristics that necessitate specific pasteurization parameters. These variations are driven by factors such as moisture content, nutrient density, and the presence of inherent microorganisms. The following table provides a comparative overview of optimal temperatures and times for some commonly used substrates, offering a practical guide for cultivators.

| Substrate Type | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Optimal Temperature (°F) | Typical Holding Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coco Coir | 60-70 | 140-158 | 1-2 hours | Generally low in nutrients, making it less prone to contamination. High moisture content is common. |

| Straw (chopped) | 65-75 | 149-167 | 1-2 hours | Nutrient-rich, requires thorough pasteurization to reduce competing organisms. Often soaked prior to pasteurization. |

| Sawdust (hardwood) | 60-70 | 140-158 | 1-2 hours | Can be supplemented with grains or other nutrients, which increases contamination risk. |

| Grain (e.g., rye, millet) | 121 (autoclaved) | 250 (autoclaved) | 90 minutes | Requires sterilization (autoclaving) rather than pasteurization due to high nutrient content and density. |

| Manure-based substrates | 65-75 | 149-167 | 1-2 hours | Highly nutritious and prone to contamination; careful pasteurization is critical. |

Challenges with Nutrient-Rich Substrates

Nutrient-rich substrates, such as straw, sawdust supplemented with grains, or manure-based mixtures, present a unique set of challenges during pasteurization. Their high nutrient content makes them an attractive food source not only for mushroom mycelium but also for a wide array of competing microorganisms, including bacteria and molds. This abundance of readily available food can lead to rapid colonization by contaminants if pasteurization is not executed effectively.The primary challenge is achieving a balance: killing off undesirable organisms without denaturing the essential nutrients that the mushroom mycelium needs to thrive.

Over-pasteurization can degrade proteins and sugars, rendering the substrate less nutritious. Conversely, under-pasteurization leaves behind too many viable competitor organisms, which will quickly outcompete the slow-growing mushroom mycelium.Potential solutions involve precise temperature and time control. For instance, using a “hot water bath” method for straw can be effective. This involves submerging the straw in water heated to the target temperature for the specified duration.

For bulk substrates like sawdust or manure, a “bucket tek” or steam pasteurization can be employed, where steam is used to heat the substrate to the desired temperature. Maintaining optimal moisture levels is also critical; overly wet substrates can create anaerobic conditions that favor certain bacteria. It is also beneficial to inoculate the pasteurized substrate as soon as it has cooled to colonization temperature, minimizing the window of opportunity for airborne contaminants to establish themselves.

Best Practices for Species-Specific Pasteurization

While general guidelines exist, tailoring pasteurization to specific mushroom species can significantly enhance success rates. Different species have varying levels of aggression in their mycelial growth and their susceptibility to common contaminants. For example, species that colonize rapidly, like Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.), may tolerate slightly less stringent pasteurization or can recover more quickly from minor contamination issues compared to slower-growing species.For species known to be particularly sensitive or slow-colonizing, such as certain gourmet or medicinal mushrooms, it is often advisable to err on the side of caution.

This might involve slightly extending the pasteurization time at the lower end of the optimal temperature range, or ensuring an even more thorough reduction of competitor organisms. For instance, when cultivating Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) on sawdust blocks, ensuring complete saturation and proper steam pasteurization is paramount to prevent the growth of Trichoderma, a common green mold contaminant.Conversely, for highly aggressive colonizers like certain strains of Oyster mushrooms, a slightly shorter pasteurization time might be sufficient, provided the temperature is consistently maintained within the optimal range.

It’s also important to consider the substrate’s moisture content relative to the species’ preference. Some species thrive in wetter conditions, while others prefer a slightly drier substrate, which can also influence contamination resistance and therefore the pasteurization requirements. Researching the specific needs and known vulnerabilities of the mushroom species you are cultivating is a fundamental best practice.

Preventing Re-contamination Post-Pasteurization

Once your substrate has been successfully pasteurized, the critical next step is to prevent any unwanted microorganisms from compromising your hard work. This phase requires meticulous attention to detail and a sterile workflow to ensure the viability and health of your cultivated organisms. The goal is to create a barrier against airborne contaminants and to handle the substrate with the utmost care.The integrity of your pasteurized substrate hinges on maintaining a sterile environment throughout the cooling and inoculation processes.

Any lapse in cleanliness or proper handling can introduce mold spores, bacteria, or other competing organisms, leading to failed grows or significant yield reductions. Therefore, adopting strict protocols is not merely a suggestion but a necessity for successful cultivation.

Minimizing Airborne Contamination Immediately After Pasteurization

The period immediately following pasteurization is when the substrate is most vulnerable to airborne contaminants. As the substrate cools, it creates convection currents that can draw in surrounding air, along with any microbial life it carries. Implementing specific procedures during this cooling phase is paramount to creating a clean environment.Here are crucial steps to take:

- Immediate Sealing: As soon as the pasteurization process is complete and the substrate has reached a safe handling temperature (typically below 100°F or 38°C, depending on the method), it should be immediately sealed. This prevents ambient air from entering the container or bag.

- Controlled Cooling Environment: If possible, allow the substrate to cool within the pasteurization vessel or in a designated clean space. Avoid opening the vessel unnecessarily until it is time for transfer.

- Air Filtration: For highly sensitive applications, consider cooling the substrate in a space equipped with HEPA filters to significantly reduce airborne particulate matter.

- Minimizing Air Exchange: Keep doors and windows closed in the area where the substrate is cooling and being transferred. Limit foot traffic and unnecessary movement, as this can stir up dust and spores.

- Surface Sterilization: Ensure all surfaces in the vicinity of the cooling substrate are thoroughly cleaned and, if appropriate, sterilized with a disinfectant solution before and during the cooling process.

Safely Transferring Pasteurized Substrate into Sterile Containers or Bags

The transfer of pasteurized substrate into its final growing containers or bags is a critical juncture where contamination risks are high. This process demands a sterile workspace and careful technique to avoid introducing unwanted microbes.Techniques for safe transfer include:

- Sterile Workspace Preparation: Before beginning the transfer, thoroughly clean and disinfect your workspace. This can involve wiping down all surfaces with isopropyl alcohol (70%) or a similar disinfectant. A still air box (SAB) or a laminar flow hood (LFH) is highly recommended for this step to create a localized sterile environment.

- Sanitizing Tools: All tools used for scooping, transferring, or manipulating the substrate, such as spatulas, scoops, or funnels, must be sterilized. This can be achieved by flaming with a torch (allowing it to cool), soaking in isopropyl alcohol, or autoclaving.

- Handling Containers and Bags: Ensure that the containers or bags you are transferring the substrate into are also sterile. If using autoclavable bags, they should be sterilized along with the substrate or separately. Jars should be sterilized via autoclaving or boiling.

- Minimizing Exposure Time: Work quickly and efficiently during the transfer to minimize the amount of time the pasteurized substrate is exposed to the air. Open bags or containers only when immediately ready to fill them.

- Proper Filling Technique: Avoid touching the inside surfaces of the containers or bags with your hands or non-sterilized tools. Gently scoop or pour the substrate, filling the containers to the appropriate level without over-packing, which can impede gas exchange.

Maintaining a Clean Environment During the Inoculation Phase

The inoculation phase, where you introduce your chosen culture (e.g., mycelium spawn) to the pasteurized substrate, is arguably the most sensitive stage. At this point, the substrate is nutrient-rich and ready for colonization, making it an ideal medium for both your desired organism and any contaminants that might be present.The importance of maintaining a clean environment during inoculation cannot be overstated.

A contaminated inoculation will almost certainly lead to a failed grow. Therefore, strict adherence to sterile techniques is essential.Key practices for a clean inoculation environment include:

- Sterile Workspace: Similar to the transfer process, the inoculation should ideally be performed within a still air box or a laminar flow hood. If these are not available, choose the cleanest, draft-free room possible and thoroughly disinfect all surfaces.

- Personal Hygiene: Wash your hands thoroughly with soap and water and then sanitize them with isopropyl alcohol before beginning. Consider wearing sterile gloves and a face mask to prevent the introduction of microbes from your breath or skin.

- Sterilizing Inoculation Tools: Any tools used to introduce the culture, such as syringes, scalpels, or inoculation loops, must be sterilized. For syringes, this typically involves flame sterilization of the needle. For scalpels and loops, flaming or soaking in alcohol followed by flaming is common.

- Handling Cultures: When working with agar plates or liquid cultures, minimize the time they are open. Use sterile techniques to transfer the culture material efficiently and accurately.

- Minimizing Air Movement: Avoid creating drafts or significant air movement in the inoculation area. Do not open and close doors or windows unnecessarily.

Methods for Sealing and Storing Pasteurized Substrate to Preserve Its Integrity

Proper sealing and storage are the final steps in protecting your pasteurized substrate until it is ready for inoculation. These methods are designed to maintain the sterile conditions established during pasteurization and transfer, preventing the ingress of contaminants over time.Methods for effective sealing and storage include:

- Bag Sealing: For substrates packaged in grow bags, a secure seal is crucial. This is often achieved using impulse sealers, which melt and fuse the plastic, creating an airtight and sterile barrier. Alternatively, heat-resistant tape can be used, but an impulse seal is generally more reliable. Ensure the seal is complete and without pinholes.

- Container Sealing: Jars or other rigid containers should be sealed with their lids. For autoclaved jars, the lids are typically applied loosely during sterilization to allow for gas exchange, and then tightened once cooled, or a filter patch is incorporated into the lid. If a filter patch is not used, the lid should be secured tightly after cooling. Some growers may also opt to cover the lid with micropore tape or aluminum foil after tightening to provide an extra layer of protection, though this should be done in a sterile environment.

- Storage Environment: Store pasteurized substrate in a cool, dark, and dry location. Avoid areas with high humidity or fluctuating temperatures, as these conditions can encourage condensation within the container or bag, creating an environment conducive to microbial growth.

- Protection from Pests: Ensure the storage area is free from insects and rodents, which can carry and introduce contaminants.

- Monitoring for Contamination: Periodically inspect stored substrate for any signs of contamination, such as unusual colors, odors, or fuzzy growth that is not your intended organism. If contamination is suspected, it is best to discard the affected substrate to prevent it from spreading.

“The success of your cultivation is directly proportional to the sterility maintained throughout the entire process, especially in the critical post-pasteurization and inoculation phases.”

Equipment and Safety for Pasteurization

Successfully pasteurizing your substrate is a critical step in preventing unwanted microbial contamination. This process requires specific equipment and a strong commitment to safety. Understanding the necessary tools and adhering to safety protocols will ensure both the effectiveness of your pasteurization and your well-being.The equipment used for substrate pasteurization varies depending on the chosen method, whether it’s a low-tech approach or a more sophisticated setup.

Regardless of the method, safety is paramount when dealing with elevated temperatures and potentially hazardous materials. Implementing proper safety measures protects you from burns, steam inhalation, and other risks.

Essential Equipment for Pasteurization Methods

To effectively pasteurize your substrate, having the right equipment is crucial. The specific tools needed will depend on whether you are using a hot water bath, steam, or an oven. Having these items readily available will streamline the process and contribute to successful results.Here is a list of essential equipment commonly used for various pasteurization methods:

- For Hot Water Bath Pasteurization:

- Large, heat-resistant container (e.g., stock pot, cooler) capable of holding your substrate and water.

- Thermometer (digital or dial) to accurately monitor water temperature.

- Heat-resistant gloves for handling hot items.

- Substrate bags or containers that can withstand heat.

- A method for submerging substrate fully, such as a rack or weight.

- For Steam Pasteurization:

- Large pot with a lid that can accommodate a steaming rack or basket.

- Steaming rack or basket to keep the substrate elevated above the boiling water.

- Water source to create steam.

- Timer to ensure the correct steaming duration.

- Heat-resistant gloves.

- Substrate bags or containers that allow for steam penetration.

- For Oven Pasteurization:

- Oven (conventional or convection) with accurate temperature control.

- Oven-safe trays or containers for the substrate.

- Thermometer (oven-safe probe thermometer is ideal) to monitor internal substrate temperature.

- Heat-resistant gloves.

- Aluminum foil to cover trays if needed.

Safety Precautions During Pasteurization

Working with high temperatures, whether from hot water, steam, or ovens, poses inherent risks. It is vital to implement strict safety protocols to prevent injuries. These precautions are designed to protect you from burns, scalding, and other potential hazards associated with the pasteurization process.Adhering to these safety measures will create a safer working environment and help ensure the success of your pasteurization efforts.

Always prioritize safety when working with heat. Assume all equipment and materials are hot until proven otherwise.

When working with hot water, steam, or ovens for pasteurization, observe the following safety precautions:

- Hot Water: Handle hot water with extreme caution. Avoid splashing and always use heat-resistant gloves when submerging or removing items from hot water. Ensure the container is stable to prevent tipping.

- Steam: Be aware of steam burns, which can be severe. Never place your hands or face directly over vents or openings where steam is escaping. Allow steam to dissipate before opening lids. Use oven mitts or heat-resistant gloves when handling items that have been steamed.

- Ovens: Use oven mitts or heat-resistant gloves when placing or removing items from a hot oven. Be mindful of the hot surfaces inside the oven. Ensure proper ventilation if any unusual fumes are detected.

- General: Keep flammable materials away from heat sources. Ensure good ventilation in the area where you are pasteurizing. Have a first-aid kit readily accessible for minor burns.

Importance of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

The use of appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is non-negotiable when pasteurizing substrate. PPE acts as a crucial barrier between you and the potential hazards of the process, significantly reducing the risk of injury. Investing in and consistently using the correct PPE is a fundamental aspect of safe pasteurization.Wearing the right PPE demonstrates a commitment to personal safety and a professional approach to the task.

- Heat-Resistant Gloves: Essential for handling hot containers, tools, and the substrate itself. Look for gloves made from materials like silicone, Kevlar, or thick cotton that offer good insulation.

- Eye Protection: Safety glasses or goggles should be worn to protect your eyes from splashes of hot water or potential debris.

- Long Sleeves and Pants: Wearing long sleeves and pants made from sturdy materials can offer an additional layer of protection against accidental burns and splashes.

- Closed-Toe Shoes: Protect your feet from spills and dropped items.

Cleaning and Maintaining Pasteurization Equipment

The longevity and hygienic integrity of your pasteurization equipment depend heavily on regular cleaning and maintenance. Proper care ensures that your equipment functions optimally and, more importantly, does not become a source of contamination itself. A clean environment is fundamental to successful pasteurization.Implementing a routine cleaning schedule will not only extend the life of your equipment but also contribute to the overall success of your pasteurization efforts.

- Immediate Post-Use Cleaning: After each use, thoroughly clean all equipment with hot, soapy water. Remove any residual substrate or debris.

- Drying: Ensure all equipment is completely dry before storing. Moisture can encourage microbial growth.

- Sanitization: Periodically sanitize your equipment, especially if it comes into direct contact with the substrate. This can be done with a diluted bleach solution (rinse thoroughly afterward) or a food-grade sanitizer.

- Inspection: Regularly inspect your equipment for any signs of wear, damage, or corrosion. Replace any damaged parts immediately.

- Storage: Store equipment in a clean, dry, and dust-free area.

Assessing Pasteurization Success

Effectively determining whether your substrate has been successfully pasteurized is a critical step in preventing contamination and ensuring a healthy growing environment. This assessment goes beyond simply completing a heating process; it involves keen observation and, in some cases, testing to confirm that harmful microorganisms have been significantly reduced while beneficial ones remain viable. A successful pasteurization aims for a balance, eliminating competitors without sterilizing the substrate entirely.Visual inspection is the first line of defense in assessing pasteurization success.

While not a definitive scientific measure, it can provide valuable clues about the substrate’s condition post-treatment. Look for a substrate that appears consistent in color and texture, without any unusual discoloration or clumping that might indicate the presence of active mold or bacterial colonies. The smell should also be neutral or pleasantly earthy, not sharp, acrid, or sour, which are common indicators of undesirable microbial activity.

Visual Inspection Indicators

A successful pasteurization typically results in a substrate that is uniformly moist but not waterlogged. It should feel pliable and cohesive. Any signs of slime, unusual wetness in patches, or the presence of visible fuzzy growth (mold) are strong indicators of incomplete pasteurization or immediate re-contamination. Similarly, a foul or ammonia-like odor suggests bacterial spoilage, which pasteurization should have prevented.

Indicators of Incomplete Pasteurization or Re-contamination

The presence of green, black, or vibrant colored molds on the surface or within the substrate is a clear sign that pasteurization was insufficient or that the substrate has been exposed to contaminants after the process. Bacterial contamination often manifests as a slimy texture, a sour or cheesy smell, or a mushy consistency. If the substrate appears overly dry or brittle, it might suggest that the pasteurization temperature was too high or applied for too long, potentially damaging beneficial organisms or altering the substrate’s structure negatively.

Methods for Testing Pasteurization Efficacy

While visual cues are helpful, more rigorous testing can provide greater confidence, especially for large-scale operations or when dealing with sensitive cultures. A common and practical method is the ” Agar Test” or “Spawn Run Test” on a small scale.

To conduct a spawn run test:

- Prepare a small, sterilized container (e.g., a glass jar with a breathable lid).

- Fill this container with a sample of the pasteurized substrate.

- Introduce a small amount of sterile grain spawn (inoculated with a known, healthy culture).

- Incubate this test container under optimal conditions for the spawn to colonize.

This test allows you to observe how well the beneficial spawn colonizes the substrate without being outcompeted by contaminants. If the spawn colonizes rapidly and healthily, it strongly suggests successful pasteurization. Conversely, if contamination appears quickly or the spawn struggles to colonize, it indicates an issue with the pasteurization process or post-pasteurization handling.Another approach, though more laboratory-intensive, involves taking samples of the pasteurized substrate and plating them on agar.

Incubating these agar plates will reveal the types and quantities of microorganisms present. A successful pasteurization will show minimal to no growth of common contaminants like molds and bacteria, or only a very low level of expected beneficial microbes.

“A successful pasteurization aims to reduce the microbial load to a manageable level, allowing desirable organisms to thrive while inhibiting the growth of aggressive competitors.”

Conclusive Thoughts

In conclusion, the journey through substrate pasteurization reveals it as a vital, yet accessible, step in achieving optimal cultivation results. By understanding the underlying scientific principles, choosing the right method for your specific needs, and diligently preventing re-contamination, you empower yourself to create the ideal environment for your chosen organisms to thrive. Embrace these practices, and witness the remarkable difference they make in your growing endeavors.