How to Identify and Stop Overlay on Your Substrate sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail with formal and friendly language style and brimming with originality from the outset.

Understanding and managing substrate overlays is a critical aspect of maintaining material integrity and performance across a wide range of applications. This comprehensive guide delves into the nuances of what constitutes an overlay, the common materials involved, and the typical scenarios leading to their formation. We will explore the significant negative impacts these unwanted layers can have on a substrate’s functionality and longevity, providing a foundational understanding for effective management.

Understanding Substrate Overlays

Understanding substrate overlays is a critical first step in identifying and mitigating their detrimental effects. An overlay, in this context, refers to any unintended layer of material that forms on or adheres to the surface of a substrate. These layers can significantly alter the substrate’s properties, leading to performance degradation and potential structural issues. A thorough comprehension of what constitutes an overlay, the materials involved, and the circumstances under which they arise is essential for effective problem-solving.The presence of an overlay is not always immediately obvious and can manifest in various forms, often subtly impacting the intended functionality of the underlying material.

Recognizing these phenomena is key to maintaining the integrity and optimal performance of your substrates across diverse applications.

Fundamental Concept of a Substrate Overlay

A substrate overlay is essentially an unwanted film or deposit that accumulates on the surface of a base material. This layer can be a residue from processing, a contaminant introduced during handling, or a byproduct of a chemical reaction. The overlay acts as an additional barrier, separating the substrate from its intended environment or from subsequent processing steps. Its thickness can range from a few nanometers to several micrometers, and its composition can vary widely.

Common Materials Forming Overlays

A diverse array of materials can form overlays, depending on the specific substrate and the surrounding environment. These materials often include organic residues, inorganic precipitates, or even unintended layers of the substrate material itself from a previous processing stage.To illustrate the variety, consider the following common types of overlay-forming materials:

- Organic Residues: These can be oils, greases, polymers, or particulate matter from manufacturing processes, handling, or environmental contamination. For instance, fingerprints left on a semiconductor wafer during fabrication can act as an organic overlay.

- Inorganic Precipitates: Salts, metal oxides, or other mineral deposits can form overlays, particularly in wet processing environments or when dealing with solutions containing dissolved solids. Scale buildup in water pipes is a classic example of an inorganic overlay.

- Unintended Material Deposition: In some manufacturing processes, a thin layer of the material intended for a different component or a previous stage can inadvertently deposit onto the target substrate. This is common in thin-film deposition processes where overspray or particle shedding can occur.

- Reaction Byproducts: Chemical reactions occurring on or near the substrate surface can generate insoluble byproducts that adhere to the surface. For example, corrosion products on metal surfaces are a form of overlay.

Typical Scenarios for Overlay Occurrence

Overlays are frequently encountered in manufacturing, processing, and even in the end-use environment of a substrate. The specific scenarios are highly dependent on the nature of the substrate and its intended application.Typical scenarios where substrate overlays are likely to occur include:

- Manufacturing and Fabrication Processes: This is perhaps the most common area. Processes such as cleaning, etching, coating, plating, and printing can all inadvertently lead to overlay formation if not meticulously controlled. For example, incomplete rinsing after a cleaning step can leave behind detergent residue.

- Handling and Assembly: Human contact, especially without proper cleanroom protocols, can introduce oils, dust, and other contaminants. Transferring components between different stages of assembly without adequate protection can also lead to contamination.

- Environmental Exposure: Substrates exposed to the atmosphere, water, or other environments can accumulate dust, pollutants, or biological matter over time. Outdoor structural components are prone to developing layers of dirt and grime.

- Storage and Transportation: Improper packaging or storage conditions can allow for the ingress of contaminants or the degradation of packaging materials, leading to overlays on the substrate surface.

Potential Negative Impacts of Overlays

The presence of an overlay, even a very thin one, can have profound negative consequences on the performance, reliability, and longevity of a substrate. These impacts stem from the overlay’s interference with the intended physical, chemical, or electrical properties of the substrate.The potential negative impacts of overlays on substrate performance and integrity are significant and can manifest in several ways:

- Altered Surface Properties: Overlays can change the surface energy, wettability, adhesion characteristics, and friction of the substrate. For instance, an oily overlay on a bonding surface will prevent proper adhesion of an adhesive.

- Impaired Electrical Conductivity/Insulation: In electronic applications, an overlay can create an unintended resistive or capacitive layer, disrupting signal integrity, causing short circuits, or increasing power consumption. A thin oxide layer on a conductive contact can dramatically increase resistance.

- Reduced Thermal Transfer: Overlays can act as thermal insulators, hindering the efficient dissipation or transfer of heat, which can lead to overheating and component failure in electronic devices or machinery.

- Compromised Chemical Reactivity: For substrates intended for chemical processes or catalysis, an overlay can block active sites, preventing or slowing down desired reactions.

- Mechanical Weakness and Failure: Overlays can act as stress concentrators, initiating cracks or delamination, especially under mechanical load. They can also reduce the shear strength of bonded joints.

- Aesthetic Degradation: In visible applications, overlays can cause discoloration, hazing, or staining, detracting from the product’s appearance and perceived quality.

Visual Identification Techniques

Observing a substrate with a keen eye is a fundamental step in identifying the presence of an overlay. While some overlays might be immediately apparent, others can be quite subtle, requiring careful examination under specific conditions. This section will guide you through the various visual cues to look for and how to optimize your inspection process.

Subtle Visual Cues of Overlay Presence

Overlays, especially those applied with precision or designed to mimic the original substrate, can present with nuanced visual discrepancies. Recognizing these subtle indicators is crucial for accurate identification. These cues often manifest as alterations in the substrate’s surface characteristics.

- Discoloration: Look for any deviation from the expected or uniform color of the substrate. This could include faint streaks, patches of slightly different hues, or a general unevenness in coloration that doesn’t correspond to the substrate’s inherent properties.

- Texture Changes: An overlay might introduce a different surface texture. This could be a difference in glossiness, a slightly rougher or smoother feel, or the presence of subtle patterns or grain that are not part of the original material.

- Opacity Variations: Observe how light interacts with the substrate. An overlay might create areas of reduced or increased opacity, leading to a less uniform translucency or a visible difference in how light passes through or reflects off the surface.

- Edge Anomalies: Pay close attention to the edges of the substrate. Overlays may not perfectly adhere to the edges, leading to slight lifting, a visible seam, or a change in the edge profile.

- Surface Imperfections: Bubbles, wrinkles, or delamination beneath the surface can be indicative of an overlay. These are often more noticeable when viewed at an angle or under specific lighting.

Influence of Lighting Conditions on Visibility

The way light falls on a substrate can dramatically alter the visibility of an overlay. Strategic use of lighting can highlight imperfections and textural differences that might otherwise go unnoticed. Experimenting with different light sources and angles is therefore a critical part of the visual inspection process.

When inspecting for overlays, consider the following lighting techniques:

- Direct, Bright Light: A strong, direct light source, such as a focused LED lamp, can cast sharp shadows and accentuate surface irregularities, making textures and minor bumps more apparent.

- Angled Light (Raking Light): Shining a light source at a shallow angle across the surface is particularly effective at revealing subtle changes in texture, such as ripples, waves, or slight undulations that an overlay might introduce.

- Diffused Light: Soft, diffused light, like that from a cloudy sky or a light box, can minimize harsh shadows and reveal underlying color variations or inconsistencies in opacity more clearly.

- Backlighting: For translucent substrates, shining light from behind can reveal variations in thickness or the presence of embedded materials within an overlay.

Visual Inspection Checklist for Different Substrate Types

The specific points to inspect can vary depending on the nature of the substrate. This checklist provides a starting point for common substrate types, emphasizing the unique visual cues to seek.

For Flat, Rigid Substrates (e.g., Printed Circuit Boards, Glass Panels):

These substrates often require meticulous examination for surface uniformity.

| Inspection Point | Potential Overlay Indicators | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Uniformity | Inconsistent sheen, slight variations in color, visible lines or seams. | Check under angled light for textural anomalies. |

| Edge Integrity | Visible overlap, adhesive residue, or a distinct layer at the edges. | Magnification may be helpful. |

| Component Mounting Points | Areas around solder pads or mounting holes may show signs of a different material or thickness. | Look for signs of disturbance or alteration. |

| Markings and Text | Overlaid text or markings might appear slightly raised, have a different font rendering, or exhibit a different level of clarity compared to the original. | Compare to known authentic markings. |

For Flexible Substrates (e.g., Films, Flexible PCBs):

Flexibility can introduce unique challenges and indicators of overlays.

| Inspection Point | Potential Overlay Indicators | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Smoothness | Wrinkles, bubbles, or areas where the overlay does not conform perfectly to the substrate. | Gently flex the substrate to reveal adherence issues. |

| Transparency/Translucency | Uneven clarity, visible layers, or a change in the degree of light transmission. | Backlighting is particularly effective here. |

| Color Consistency | Patches of differing color or a mottled appearance. | Inspect under various lighting conditions. |

| Flexibility Behavior | Areas that bend or crease differently, indicating a change in material properties. | Observe how the substrate reacts to manipulation. |

For Textured or Patterned Substrates (e.g., Decorative Laminates, Some Composites):

Distinguishing an overlay from the original texture requires careful comparison.

| Inspection Point | Potential Overlay Indicators | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern Alignment | Misalignment or a subtle shift in the pattern compared to the substrate’s underlying structure. | Look for repeating elements that don’t match. |

| Texture Depth and Consistency | Variations in the depth or uniformity of the texture, or a feel that is inconsistent with the expected material. | Compare tactile feel with visual cues. |

| Sheen Differences | An overlay might have a different gloss level that clashes with the original texture. | Observe reflections under angled light. |

| Seams and Edges | Overlays on textured surfaces can be harder to conceal at the edges, sometimes resulting in a visible lip or transition. | Magnification is often necessary. |

Non-Destructive Testing for Overlay Detection

While visual inspection offers initial clues, a definitive understanding of subsurface conditions often requires more advanced techniques. Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods are invaluable for identifying anomalies, such as overlays, without causing any damage to the substrate. These methods employ various physical principles to probe beneath the surface and reveal deviations from the expected material properties or structure.These techniques are crucial for assessing the integrity and composition of materials, especially in critical applications where failure can have significant consequences.

By detecting subsurface issues like overlays, NDT allows for informed decision-making regarding maintenance, repair, or replacement strategies, ultimately saving time and resources.

Ultrasonic Testing Principles

Ultrasonic testing (UT) utilizes high-frequency sound waves to detect internal flaws and measure material thickness. The principle relies on transmitting sound pulses into the material and analyzing the reflected or transmitted waves. When a sound wave encounters a boundary between two different materials, such as the interface between the substrate and an overlay, a portion of the wave is reflected.

The time it takes for the reflected wave to return to the transducer, and its amplitude, provide information about the location and nature of the discontinuity.The frequency of the ultrasonic waves is selected based on the material properties and the expected depth of inspection. Lower frequencies penetrate deeper but offer lower resolution, while higher frequencies provide better resolution but have limited penetration.

For overlay detection, specific frequencies are chosen to optimize the detection of the interface between the substrate and the overlay material.

The analysis of reflected ultrasonic signals allows for the characterization of internal defects and material interfaces.

Eddy Current Testing Principles

Eddy current testing (ECT) is an electromagnetic method used to detect surface and near-surface flaws in conductive materials. The technique involves inducing alternating electrical currents, known as eddy currents, in the material using a coil carrying an alternating current. These eddy currents generate their own magnetic field, which opposes the field of the excitation coil. Any discontinuity or change in the material’s conductivity, permeability, or geometry, such as an overlay, will disrupt the flow of eddy currents, altering the impedance of the coil.The changes in the coil’s impedance are measured and analyzed to indicate the presence and characteristics of the subsurface anomaly.

The depth of penetration of eddy currents is limited and depends on the frequency of the applied current and the conductivity of the material. Higher frequencies are more sensitive to surface conditions, while lower frequencies can detect deeper flaws.

Comparison of Non-Destructive Approaches

Each non-destructive testing method possesses unique strengths and limitations that make them suitable for different applications. Understanding these differences is key to selecting the most appropriate technique for overlay identification.

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT):

- Strengths: Can detect both surface and subsurface flaws, provides accurate depth measurement, versatile for various material types (metals, plastics, composites), relatively portable.

- Limitations: Requires good acoustic coupling (often a couplant gel is needed), can be challenging on rough or complex surfaces, interpretation of signals may require experienced personnel.

- Eddy Current Testing (ECT):

- Strengths: Highly sensitive to surface and near-surface flaws, rapid inspection, no couplant required, effective for detecting cracks, seams, and material variations.

- Limitations: Limited to conductive materials, penetration depth is restricted, can be affected by lift-off (distance between the probe and the surface), less effective for detecting non-conductive overlays or significant thickness variations.

Basic Non-Destructive Test Procedure for Overlay Identification

Performing a basic non-destructive test to identify an overlay typically involves a systematic approach. The following steps Artikel a general procedure, which can be adapted based on the specific NDT method chosen and the material being inspected.

- Preparation:

- Ensure the surface of the substrate is clean and free from any contaminants that could interfere with the test. This may involve light grinding or cleaning.

- Familiarize yourself with the specific NDT equipment and its operating manual.

- Calibrate the equipment using known standards or reference samples that simulate the expected material properties and potential overlay conditions.

- Test Execution:

- For Ultrasonic Testing: Apply a suitable couplant to the surface. Place the ultrasonic transducer on the surface and initiate the sound wave transmission. Observe the display for indications of reflected signals that correspond to the interface between the substrate and a potential overlay. The timing and amplitude of these reflections are critical for interpretation.

- For Eddy Current Testing: Position the eddy current probe near the surface of the substrate. Energize the probe and observe the instrument’s output, which typically indicates changes in impedance. Significant deviations from the baseline reading can suggest the presence of an overlay or other subsurface anomaly.

- Data Interpretation:

- Analyze the signals or readings obtained from the NDT instrument. Look for characteristic patterns that indicate the presence of a distinct interface.

- Compare the observed indications with the calibration standards or known baseline readings to confirm the presence and approximate thickness of the overlay.

- Document all findings, including the location of any detected anomalies, the readings obtained, and the parameters used during the test.

- Verification (if necessary):

- In cases where the NDT results are ambiguous or require confirmation, consider using a complementary NDT method or, if permissible, a limited destructive test (e.g., a small core sample) at a non-critical location to verify the findings.

Material Analysis and Characterization

Once an overlay is suspected, a thorough material analysis is crucial for definitive identification and understanding its properties. This phase involves employing a suite of techniques to dissect the chemical composition, physical structure, and dimensional characteristics of the suspected overlay and its underlying substrate. The insights gained here are fundamental for assessing the integrity of the bond, the nature of the overlay material, and its potential impact on the substrate’s performance.This section delves into the methodologies used to characterize the overlay material, determine its thickness, and prepare samples for detailed microscopic examination, emphasizing how spectral analysis aids in differentiating overlay components from the base substrate.

Material Composition Analysis

Determining the exact chemical makeup of a suspected overlay is paramount for its identification. Various analytical techniques can be employed to achieve this, providing detailed insights into the elements and compounds present.Here are several key techniques for characterizing the material composition:

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX/EDS): This technique is often coupled with Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). When a high-energy electron beam strikes the sample, it excites the atoms, causing them to emit characteristic X-rays. The energy of these X-rays is unique to each element, allowing for qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis of the overlay material. This is highly effective for identifying metallic overlays or inorganic coatings.

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): XPS is a surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique that measures the elemental composition and chemical state of the elements within the top 1-10 nanometers of a material. It is particularly useful for identifying organic coatings, polymers, or thin film layers where surface chemistry is critical. XPS can differentiate between different oxidation states of an element, providing deeper chemical information.

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): FTIR is excellent for identifying organic materials and polymers. It works by measuring the absorption of infrared radiation by the sample, which causes molecular vibrations. The resulting spectrum is a unique fingerprint of the material’s chemical bonds, allowing for the identification of specific polymers, resins, or organic contaminants that might form an overlay.

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): For volatile or semi-volatile organic compounds, GC-MS is a powerful tool. The sample is first separated into its components by gas chromatography, and then each component is analyzed by mass spectrometry, which determines its molecular weight and fragmentation pattern, enabling identification. This is useful for identifying organic residues or layered organic materials.

- Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES): These techniques are used for elemental analysis, particularly for metallic elements. AAS measures the absorption of light by ground-state atoms in the gaseous state, while ICP-AES measures the light emitted by atoms excited in a plasma. They are highly sensitive and can detect trace elements, which can be important for identifying specific alloy overlays or contaminants.

Overlay Thickness Determination

Accurate measurement of the overlay’s thickness is essential for understanding its impact on the substrate’s dimensions and properties, as well as for quality control and failure analysis.Methods for determining overlay thickness include:

- Microscopic Examination (Cross-Sectional Analysis): This is one of the most direct methods. A small section of the overlay and substrate is carefully cut, polished, and mounted for examination under a microscope. The interface between the overlay and substrate is clearly visible, and the thickness of the overlay layer can be measured directly using the microscope’s calibrated graticule or digital imaging software. This method provides a visual confirmation and is highly accurate for a given sample point.

- Ultrasonic Thickness Gauging: This non-destructive method uses high-frequency sound waves. A transducer emits sound pulses into the material, which travel through the overlay and reflect off the substrate. The time it takes for the sound wave to travel to the interface and back is measured. Knowing the speed of sound in the overlay material, the thickness can be calculated using the formula:

Thickness = (Velocity of Sound × Transit Time) / 2

This method is fast, non-destructive, and suitable for large areas, provided the overlay and substrate materials have different acoustic impedances.

- Eddy Current Thickness Measurement: This non-destructive technique is applicable for conductive overlays on conductive or non-conductive substrates. It relies on the principle of electromagnetic induction. A coil carrying an alternating current generates a magnetic field, which induces eddy currents in the conductive overlay. The strength and phase of these eddy currents are influenced by the overlay’s thickness and conductivity. The instrument measures these changes to determine the thickness.

- Optical Profilometry: Techniques like white light interferometry or confocal microscopy can provide highly precise, non-contact measurements of surface topography and layer thickness. These methods scan the surface and reconstruct a 3D profile, allowing for the measurement of step heights, which correspond to the overlay thickness. They are particularly useful for thin or delicate overlays where contact methods might cause damage.

Sample Preparation for Microscopic Examination

Preparing samples for microscopic examination of overlay-substrate interfaces is a critical step that ensures clear visualization and accurate analysis. Improper preparation can lead to artifacts that misrepresent the true nature of the interface.The process typically involves the following steps:

- Sectioning: A representative portion of the affected substrate and overlay is carefully cut using a low-speed diamond saw or a precision abrasive cutter. The cutting speed and coolant are important to minimize heat and mechanical damage to the interface.

- Mounting: The cut section is then mounted in a suitable epoxy resin. This provides a stable block for subsequent grinding and polishing. The choice of epoxy is important; it should have low shrinkage and good adhesion to both the overlay and substrate materials. If the materials are dissimilar (e.g., metal on ceramic), special mounting techniques might be required.

- Grinding: The mounted sample is ground using progressively finer abrasive papers (e.g., silicon carbide papers) to achieve a flat surface and remove the damage caused by sectioning. This process removes material layer by layer, ensuring that the interface is parallel to the surface being prepared.

- Polishing: After grinding, the sample is polished using diamond pastes of decreasing particle size (e.g., from 6 µm down to 0.25 µm or finer). This step is crucial for achieving a mirror-like finish, which is essential for high-magnification optical or electron microscopy. Vibratory polishing can be used for achieving the finest finishes.

- Etching (Optional but often necessary): For optical microscopy, especially when dealing with metallic interfaces, etching with a specific chemical reagent might be necessary. Etching selectively attacks different phases or reveals grain boundaries, making the microstructure and the interface more visible. The etchant must be chosen carefully to avoid preferential attack of the overlay or substrate.

Spectral Analysis for Material Differentiation

Spectral analysis techniques are invaluable for distinguishing overlay materials from the base substrate due to their unique optical or electromagnetic responses. These methods exploit the fact that different materials absorb, reflect, or emit electromagnetic radiation at characteristic wavelengths.Here’s how spectral analysis differentiates overlay materials:

- Raman Spectroscopy: Raman spectroscopy probes the vibrational modes of molecules. Each chemical compound has a unique Raman spectrum, acting as a molecular fingerprint. By analyzing the Raman spectrum of a suspected overlay and comparing it to the spectrum of the known substrate material, one can confirm whether the overlay is composed of a different substance. This technique is non-destructive and can be performed in situ or on prepared samples.

For instance, a polymer overlay on a metallic substrate would exhibit distinct Raman peaks corresponding to its molecular structure, absent in the metal’s spectrum.

- Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: As mentioned earlier, FTIR is excellent for identifying organic materials. The absorption bands in the IR spectrum correspond to specific functional groups within the molecule. If an overlay is organic (e.g., a paint, coating, or residue) and the substrate is inorganic (e.g., silicon, glass, or metal), the IR spectrum will clearly show absorption bands characteristic of the organic overlay that are absent in the substrate.

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy measures the absorption or transmission of light in the UV and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Different materials absorb and reflect light differently based on their electronic structure. For colored overlays or those with specific chromophores, UV-Vis spectroscopy can provide a spectral signature that differs significantly from the substrate. This can be useful for identifying dyes, pigments, or specific organic contaminants.

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): While primarily used for crystalline material identification, XRD can also help differentiate between overlay and substrate if they have different crystalline structures or phases. The diffraction pattern is unique to each crystalline material. If an overlay is crystalline and has a different crystal lattice than the substrate, XRD can confirm its presence and identify it. This is particularly useful for identifying inorganic overlays like ceramics or specific metal phases.

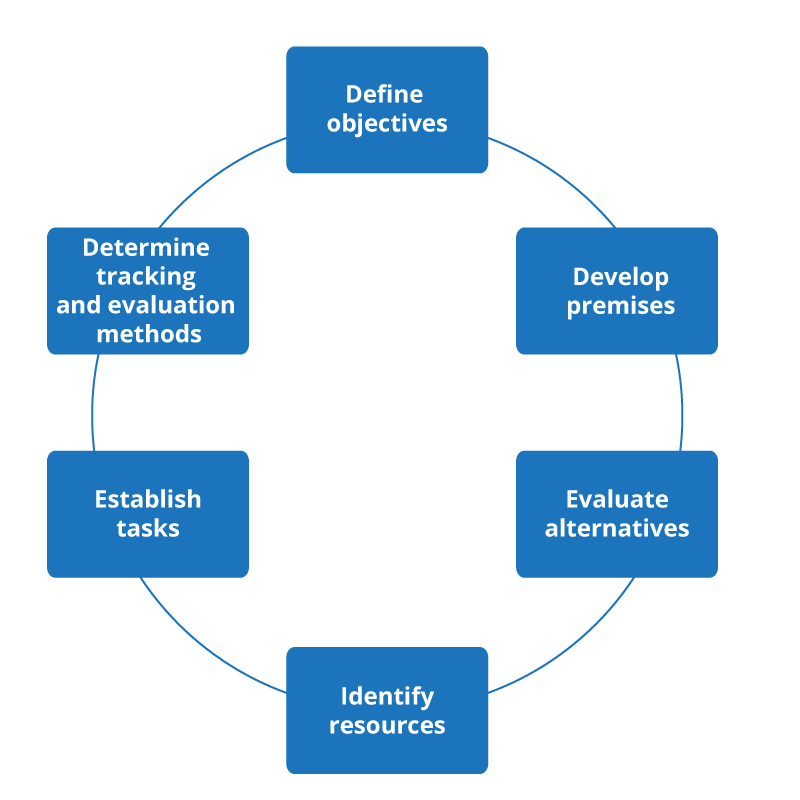

Common Causes and Prevention Strategies

Understanding the root causes of overlay formation is crucial for developing effective prevention strategies. In industrial and manufacturing environments, overlays can arise from various sources, often related to material interactions, process conditions, and environmental factors. Proactive measures, focusing on material selection, process control, and diligent maintenance, are key to minimizing these undesirable formations and ensuring substrate integrity.The accumulation of unwanted material on a substrate, commonly referred to as an overlay, can significantly compromise the performance, longevity, and aesthetic appeal of the material.

Identifying the underlying reasons for these formations allows for the implementation of targeted solutions that prevent their occurrence in the first place, rather than solely relying on detection and removal.

Root Causes of Overlay Formation

Overlay formation is typically a consequence of specific material behaviors and process parameters. These can range from the inherent properties of the materials involved to external environmental influences during manufacturing or operation.The primary contributors to overlay formation include:

- Material Incompatibility: When two materials with differing chemical or physical properties are in contact under certain conditions, one material may deposit or adhere to the surface of the other. This can be due to adhesion forces, chemical reactions, or phase changes. For example, in high-temperature processing, volatile components from one material might condense on a cooler substrate.

- Process Contamination: The presence of foreign particles or substances within the manufacturing environment can lead to their deposition onto the substrate. This can originate from dust, wear debris from machinery, or residues from previous processing steps.

- Chemical Reactions and Precipitation: In certain chemical processing environments, reactions can occur that lead to the precipitation of solid byproducts onto the substrate surface. This is common in electroplating, etching, or chemical vapor deposition processes if not precisely controlled.

- Thermal Degradation and Volatilization: When substrates or associated materials are exposed to elevated temperatures, components may degrade, volatilize, and then re-condense on cooler surfaces, forming an overlay. This is particularly relevant in polymer processing or metal annealing.

- Mechanical Wear and Transfer: In applications involving friction or contact between surfaces, wear particles from one component can be transferred and adhere to the surface of another, creating an overlay. This is often seen in bearing surfaces or sliding mechanisms.

- Environmental Exposure: In operational environments, substrates can be exposed to airborne particles, moisture, or corrosive agents that can react with the surface or deposit as layers over time.

Practical Prevention Strategies

Preventing overlay formation requires a multi-faceted approach that addresses material science, process engineering, and operational practices. Implementing these strategies can significantly reduce the likelihood of unwanted deposits.Effective prevention strategies encompass the following areas:

- Material Selection and Design: Choosing substrates and processing materials with inherent compatibility can drastically reduce overlay issues. This involves considering factors like surface energy, chemical inertness, and thermal expansion coefficients. For instance, using coatings designed to be non-reactive with the substrate can prevent chemical overlays.

- Process Parameter Optimization: Carefully controlling temperature, pressure, flow rates, and residence times in manufacturing processes can prevent conditions conducive to overlay formation. For example, maintaining precise temperature gradients can prevent unwanted condensation.

- Contamination Control: Implementing rigorous cleanroom protocols, using filtered air and water, and maintaining equipment to prevent wear debris are essential for minimizing contamination. Regular cleaning of processing equipment also plays a vital role.

- Surface Modification: Applying surface treatments or coatings that enhance substrate resistance to adhesion or chemical attack can prevent overlays. This could include passivating treatments or the application of anti-fouling coatings.

- Process Monitoring and Control: Real-time monitoring of process parameters and the use of automated control systems can detect deviations that might lead to overlay formation and allow for immediate correction.

The Role of Surface Preparation

Proper surface preparation is a foundational element in minimizing overlay formation. A clean, well-prepared substrate surface is less likely to promote adhesion of unwanted materials and is more receptive to intended surface treatments.The importance of surface preparation is underscored by its ability to:

- Remove Existing Contaminants: Thorough cleaning removes oils, greases, oxides, and particulate matter that could act as nucleation sites for overlay growth or interfere with subsequent processes.

- Enhance Surface Energy: Techniques like etching or plasma treatment can increase the surface energy of a substrate, promoting better adhesion of intended coatings and making it less susceptible to loosely adhering contaminants.

- Create a Uniform Surface: A consistent surface topography ensures that any subsequent material deposition occurs uniformly, reducing the likelihood of localized buildup that can initiate overlay formation.

- Promote Chemical Inertness: Pre-treatment processes can create a more chemically stable surface, reducing the potential for unwanted reactions with the processing environment.

Common surface preparation techniques include degreasing, mechanical cleaning (e.g., abrasive blasting), chemical cleaning, and plasma or corona treatment. The choice of method depends heavily on the substrate material and the specific manufacturing process.

Preventative Maintenance Schedules

Regular and well-structured preventative maintenance is critical for mitigating overlay issues over the long term. It ensures that equipment functions optimally and that the manufacturing environment remains conducive to defect-free production.An effective preventative maintenance schedule should include:

- Regular Equipment Inspections: Scheduled checks of processing machinery, including seals, filters, and wear parts, can identify potential sources of contamination or malfunction before they impact the substrate.

- Routine Cleaning and Calibration: Implementing a strict schedule for cleaning processing chambers, tools, and the general manufacturing area is paramount. Calibration of sensors and control systems ensures process parameters remain within specified limits.

- Filter Replacement: Regularly replacing air, liquid, and process gas filters prevents the introduction of particulate matter into the production line.

- Lubrication Management: Ensuring that lubricants used in machinery are compatible with the processing environment and are applied correctly prevents lubricant migration and contamination.

- Process Audits: Periodic audits of the manufacturing process can identify subtle deviations or emerging trends that might indicate an increased risk of overlay formation.

By integrating these maintenance activities into a proactive schedule, manufacturers can significantly reduce the incidence of unwanted overlays, thereby improving product quality and reducing costly rework or scrap.

Remediation and Removal Procedures

Successfully identifying an overlay is only the first step; the subsequent remediation and removal process is critical to restoring the substrate to its intended condition. This phase requires careful planning and execution to ensure the overlay is removed effectively without causing damage to the underlying material. The choice of method is highly dependent on the nature of both the overlay and the substrate, as well as the scale of the operation.The process of overlay removal aims to meticulously detach the foreign material from the substrate, leaving the original surface intact and ready for further treatment or reuse.

This involves understanding the adhesive properties of the overlay, the structural integrity of the substrate, and the potential for chemical or mechanical interactions between them. A well-executed removal procedure minimizes risks and maximizes the value of the substrate.

Methods for Safe and Effective Overlay Removal

Several techniques can be employed for overlay removal, each with its own advantages and limitations. The selection process should prioritize safety, efficiency, and minimal impact on the substrate.

- Mechanical Removal: This involves using physical force to detach the overlay. Common methods include scraping, grinding, or blasting. Scraping is suitable for loosely adhered or thin overlays. Grinding, using abrasive discs or wheels, is effective for more stubborn or thicker overlays but requires careful control to avoid excessive substrate abrasion. Abrasive blasting, using media like sand, glass beads, or walnut shells, can be highly effective for large areas and various overlay types, but the choice of media is crucial to prevent substrate damage.

- Thermal Removal: Heat can be used to soften or weaken the bond between the overlay and the substrate, facilitating its removal. Techniques include using heat guns, torches, or specialized heated scrapers. This method is particularly useful for adhesives or polymeric overlays that become pliable when heated. However, excessive heat can damage heat-sensitive substrates like certain plastics or composites.

- Chemical Removal: Solvents or chemical strippers can dissolve or break down the adhesive holding the overlay in place. The selection of a chemical stripper depends on the type of overlay and its bonding agent. It is essential to test the stripper on an inconspicuous area first to ensure it does not damage the substrate. Proper ventilation and personal protective equipment are paramount when using chemical agents.

- Water Jetting/Hydro-demolition: High-pressure water jets can effectively remove overlays, especially in construction and infrastructure projects. Hydro-demolition uses controlled high-pressure water to remove concrete overlays or coatings without generating dust or excessive heat, making it a safer alternative to mechanical methods in some environments.

Considerations for Choosing a Removal Technique

The optimal removal technique is a tailored decision, balancing the characteristics of both the overlay and the substrate to achieve the desired outcome with minimal collateral damage.The substrate material dictates the acceptable levels of mechanical stress, thermal exposure, and chemical interaction. For instance, a brittle substrate like ceramic or glass will be highly susceptible to mechanical impact, making abrasive blasting or aggressive grinding unsuitable.

Conversely, a robust substrate like steel can withstand more vigorous mechanical treatments. Similarly, heat-sensitive polymers or composites require gentle thermal or chemical approaches, whereas inert materials might tolerate a wider range of methods.The overlay type is equally important. Thin, flexible films might be easily peeled or dissolved, while thick, rigid coatings may necessitate grinding or blasting. The adhesive strength also plays a significant role; strong epoxies will require more aggressive methods than weaker, pressure-sensitive adhesives.

Understanding the composition of both layers is key to selecting a removal strategy that is both effective and non-destructive.

Best Practices for Post-Removal Cleaning and Surface Conditioning

Once the overlay has been removed, thorough cleaning and surface conditioning are essential to prepare the substrate for its next phase. This step ensures optimal adhesion for any subsequent coatings or treatments and prevents re-contamination.Effective cleaning removes residual overlay material, adhesive traces, and any contaminants introduced during the removal process. The chosen cleaning method should be compatible with the substrate material.

For many surfaces, a simple wash with water and mild detergent, followed by thorough rinsing and drying, is sufficient. However, for more stubborn residues, specific solvents or degreasers might be necessary.Surface conditioning may involve light abrasion, etching, or passivation, depending on the intended use of the substrate. Light sanding can remove micro-residues and create a uniform surface profile. Etching, often with mild acids, can enhance surface porosity for better adhesion.

Passivation, particularly for metals, can restore protective oxide layers.

Workflow for Assessing the Substrate After Overlay Removal

A systematic assessment workflow is crucial to confirm the integrity of the substrate after overlay removal and to identify any unintended damage. This structured approach ensures that the substrate is truly ready for its next application.The workflow typically begins with a visual inspection. This initial step involves carefully examining the entire surface for any signs of damage such as scratches, gouges, delamination, or discoloration.

Magnification tools can be employed for a more detailed inspection of the surface texture and for identifying microscopic defects.Following the visual inspection, non-destructive testing methods may be employed for a more quantitative assessment. Techniques like ultrasonic testing can detect internal delaminations or voids that might not be visible externally. Eddy current testing can be used to assess surface cracks or changes in material properties on conductive substrates.

“The integrity of the substrate is paramount; any damage introduced during remediation can compromise the performance and lifespan of the final application.”

Finally, material analysis may be performed if there is suspicion of significant substrate alteration. This could involve micro-hardness testing to check for surface hardening or softening, or chemical analysis to detect any residual contaminants that might affect future processes. A comprehensive report detailing the findings of these assessments should be generated, documenting the condition of the substrate and any necessary further actions.

Case Studies and Examples

Examining real-world scenarios provides invaluable insight into the practical challenges and successful resolutions of substrate overlay issues. These case studies demonstrate the diverse nature of overlay problems, the effectiveness of various identification techniques, and the critical importance of timely intervention. By analyzing these examples, we can better anticipate and address potential overlay situations in our own applications.The following sections present hypothetical but representative scenarios that illustrate the identification and resolution of overlay issues across different substrate types.

Each case highlights the specific substrate, the nature of the overlay, the diagnostic methods employed, and the subsequent removal or remediation process.

Scenario 1: Metallic Overlay on Ceramic Substrate

A manufacturer of specialized electronic components observed a degradation in the performance of their ceramic substrates used in high-frequency applications. Visual inspection revealed a thin, uneven layer on the surface of the ceramic, which was not part of the original design. This layer appeared slightly iridescent and had a patchy distribution.The substrate type was a high-purity alumina ceramic, essential for its electrical insulation properties and thermal stability.

The suspected overlay was a metallic contamination, likely introduced during a high-temperature firing process. Initial identification methods included optical microscopy, which confirmed the presence of a distinct surface layer with different refractive properties compared to the ceramic. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) was then employed to analyze the elemental composition of the overlay. The EDX spectrum clearly indicated the presence of copper and tin, suggesting a bronze or brass contamination.The removal process for this metallic overlay on ceramic involved a carefully controlled chemical etching technique.

A dilute nitric acid solution was used, specifically chosen for its ability to dissolve copper and tin alloys without significantly attacking the alumina ceramic. The etching was performed at a controlled temperature and for a specific duration to ensure complete removal of the overlay while minimizing substrate damage. Post-etching, the substrate was thoroughly rinsed and subjected to surface profilometry to confirm the absence of the overlay and the integrity of the ceramic surface.

Scenario 2: Polymer Coating on Metal Substrate

In the automotive industry, a batch of painted metal car panels exhibited premature paint delamination in specific areas. The affected regions showed signs of blistering and peeling, revealing an underlying layer that was different from the intended primer. This underlying layer was somewhat flexible and had a slightly rubbery texture.The substrate was a pre-treated steel panel, designed for automotive painting.

The overlay was identified as an uncured or improperly cured polymer layer, likely a contaminant from a previous processing step or a faulty application of a release agent. Visual inspection and tactile examination were the first steps. Further identification involved microscopic analysis, which revealed a distinct interfacial layer between the steel and the paint. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to characterize the chemical composition of this layer, confirming it to be a silicone-based polymer, which is known for its poor adhesion to paint systems.The remediation strategy for this polymer overlay on the metal substrate involved mechanical removal.

The delaminated paint and the underlying polymer layer were carefully abraded using fine-grit sandpaper and a low-speed orbital sander. Care was taken to avoid excessive heat generation, which could further cure or spread the polymer. After mechanical removal, the surface was thoroughly cleaned with an appropriate solvent to remove any residual polymer or abrasive debris. The panel was then re-primed and repainted according to standard automotive procedures.

Scenario 3: Oxide Layer on Semiconductor Wafer

A semiconductor fabrication facility experienced a significant increase in wafer rejects due to electrical short circuits and inconsistent device performance. Inspection of the silicon wafers revealed a thin, often discolored, layer on the wafer surface that was not part of the intended process steps. This layer appeared to be amorphous and varied in thickness.The substrate was a highly pure silicon wafer, the foundation for integrated circuits.

The overlay was identified as an unwanted silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer, possibly formed due to unintentional oxidation during handling or processing in a non-inert atmosphere. Initial identification involved optical microscopy, which showed subtle surface variations. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was employed to precisely measure the thickness and surface roughness of the suspected overlay. Crucially, ellipsometry was used to accurately determine the refractive index and thickness of the thin dielectric film, confirming it to be SiO2.The removal process for this oxide overlay on the silicon wafer required a highly selective and precise chemical etch.

A buffered hydrofluoric acid (BHF) solution was used. BHF is known to effectively etch SiO2 while having minimal impact on the underlying silicon. The concentration of HF and the etching time were meticulously controlled to achieve complete removal of the unwanted oxide layer without damaging the silicon wafer. After etching, the wafers were subjected to rigorous cleaning protocols, including RCA cleaning, to ensure a pristine surface ready for subsequent fabrication steps.

Effectiveness of Removal Techniques for Different Overlay/Substrate Combinations

The efficacy of different overlay removal techniques is highly dependent on the nature of both the overlay material and the underlying substrate. A technique that is highly effective for one combination might be detrimental to another. The following table compares the effectiveness of common removal methods across various overlay and substrate pairings, considering factors like material compatibility, selectivity, and potential for substrate damage.

| Overlay Type | Substrate Type | Removal Technique | Effectiveness Score (1-5, 5=Highly Effective) | Potential for Substrate Damage (Low/Medium/High) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Contamination (e.g., Copper, Tin) | Ceramic (e.g., Alumina) | Chemical Etching (Acidic) | 4 | Low | Requires careful selection of etchant to avoid substrate attack. |

| Polymer Coating (e.g., Silicone) | Metal (e.g., Steel) | Mechanical Abrasion (Sandpaper) | 3 | Medium | Risk of surface roughening or heat generation. |

| Oxide Layer (e.g., SiO2) | Semiconductor (e.g., Silicon) | Chemical Etching (BHF) | 5 | Low | Highly selective, but requires precise control. |

| Organic Residues (e.g., Oils, Greases) | Glass | Solvent Cleaning | 4 | Low | Effective for soluble organic materials. |

| Paint/Coating (Unwanted) | Plastic | Laser Ablation | 4 | Medium | Can be precise but risk of thermal damage to plastic. |

| Carbon Deposits | High-Temperature Alloy | Plasma Cleaning | 3 | Low | Effective for removing carbonaceous materials without significant substrate removal. |

Consequences of Ignored Overlays

The importance of early detection and prompt remediation of substrate overlays cannot be overstated. Ignoring these issues can lead to a cascade of negative consequences, significantly impacting product performance, reliability, and ultimately, economic viability. The following examples illustrate the potential repercussions of neglecting overlay problems.For instance, consider a scenario where an unintentional oxide layer forms on a silicon wafer during a critical fabrication step.

If left unaddressed, this oxide layer can act as an insulator or a barrier, preventing proper electrical contact formation during subsequent metallization processes. This results in open circuits or high-resistance connections within the integrated circuit, leading to device failure. In high-volume manufacturing, a batch of such faulty wafers can translate into millions of dollars in lost revenue and significant damage to a company’s reputation for quality.Another example involves a thin, invisible metallic contamination on a substrate used for sensitive optical coatings.

This contamination can alter the refractive index of the substrate surface, leading to scattering or absorption of light. The intended optical properties of the coating will be compromised, resulting in reduced performance of optical devices such as lenses or mirrors. In critical applications like scientific instrumentation or aerospace, such performance degradation can have severe implications, potentially leading to mission failure or inaccurate scientific data.Furthermore, a seemingly minor organic residue on a metal substrate intended for bonding can severely weaken the adhesive joint.

The organic overlay acts as a parting layer, preventing intimate contact between the adhesive and the substrate. Over time, this can lead to premature bond failure, especially under stress or environmental fluctuations. In structural applications, such as in the aerospace or automotive industries, a bond failure can have catastrophic consequences, posing significant safety risks. These examples underscore the critical need for vigilant monitoring and proactive intervention when dealing with substrate overlays.

Closing Summary

In summary, effectively addressing substrate overlays requires a multi-faceted approach, from meticulous visual inspections and advanced non-destructive testing to in-depth material analysis and proactive prevention strategies. By understanding the root causes and implementing appropriate remediation procedures, you can ensure the optimal performance and durability of your substrates, safeguarding against costly failures and enhancing the overall quality of your products and processes.