Beginning with How to Differentiate Between Spores, Spawn, and Substrate, the narrative unfolds in a compelling and distinctive manner, drawing readers into a story that promises to be both engaging and uniquely memorable.

Understanding the fundamental components of fungal life is crucial for anyone venturing into the fascinating world of mycology, particularly for cultivation. This exploration delves into the distinct roles and characteristics of spores, spawn, and substrate, illuminating how each plays an indispensable part in the fungal lifecycle and successful mushroom cultivation. By clarifying these essential elements, we aim to equip you with the knowledge to confidently navigate the initial stages of your fungal endeavors.

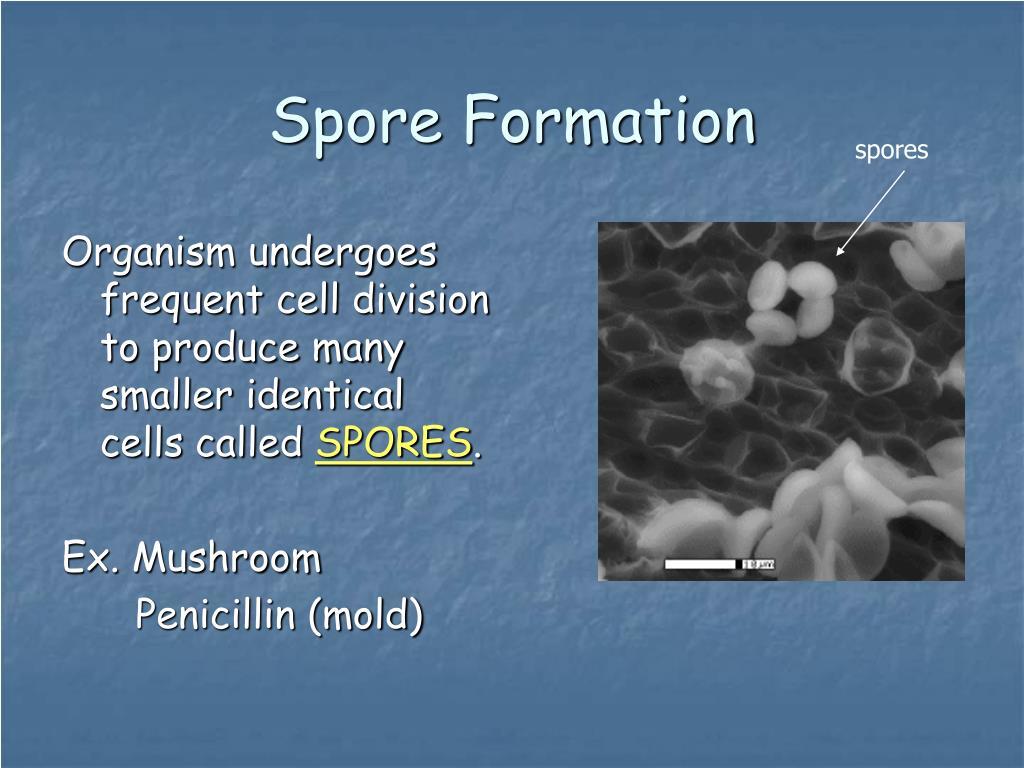

Understanding Spores: The Foundation of Fungal Life

Spores are the microscopic, reproductive units of fungi, akin to seeds in plants. They are fundamental to the life cycle of fungi, enabling their propagation and survival across diverse environments. Their production and dispersal are sophisticated biological processes that have allowed fungi to colonize virtually every habitat on Earth.Fungal spores are typically single-celled or multicellular structures produced in vast quantities.

Their primary biological role is to facilitate reproduction and ensure the continuation of the fungal species. They are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, allowing them to remain viable for extended periods until favorable conditions arise for germination.

Spore Formation and Biological Role

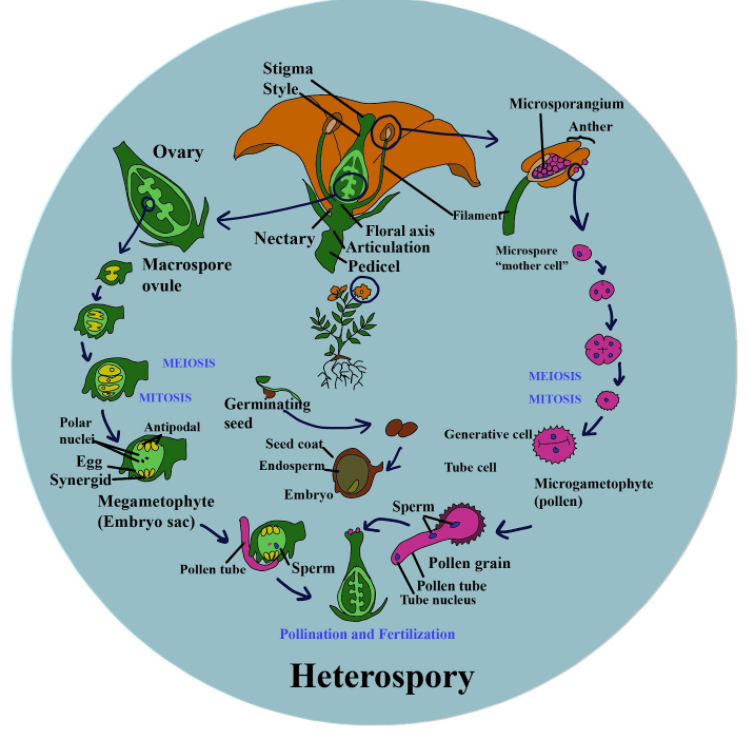

Fungal spores are produced through either asexual or sexual reproduction. Asexual spores are genetically identical to the parent fungus and are formed through processes like mitosis. They are primarily involved in rapid colonization and population growth. Sexual spores, on the other hand, result from the fusion of genetic material from two parent fungi, leading to genetic diversity within the offspring.

This diversity can enhance the adaptability of the species to changing environmental pressures.

Types of Fungal Spores

Fungal spores exhibit significant diversity in their morphology, size, and formation, reflecting their adaptation to different dispersal strategies and environments. Understanding these variations is crucial for accurate identification and appreciation of fungal biology.Here are some common types of fungal spores:

- Conidiospores (or Conidia): These are asexual spores produced exogenously (on the outside) from specialized hyphal structures called conidiophores. They are extremely common and diverse, found in molds like Penicillium and Aspergillus. Their appearance can vary greatly, from simple, single-celled structures to complex, multicellular chains.

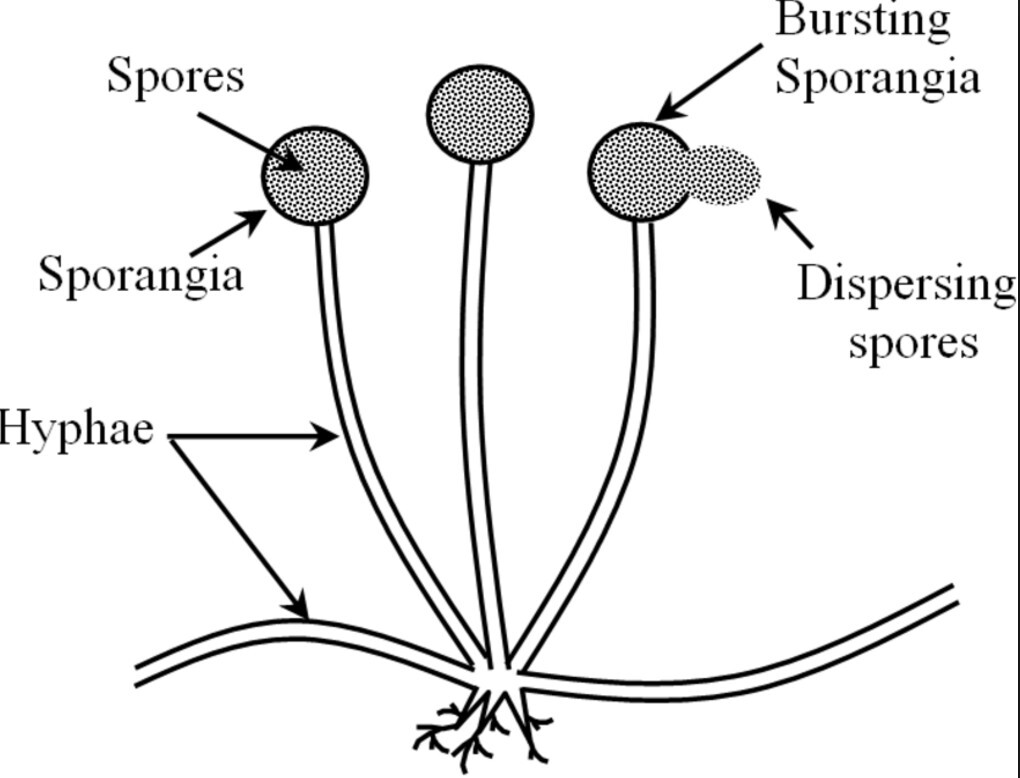

- Sporangiospores: These asexual spores are produced endogenously (within a sac-like structure) called a sporangium, which is borne on a sporangiophore. This type is characteristic of fungi in the phylum Zygomycota, such as Rhizopus (bread mold).

- Ascospores: These are sexual spores produced within a sac-like structure called an ascus. Typically, an ascus contains eight ascospores, which are formed after meiosis. Fungi that produce ascospores are known as ascomycetes, a large group that includes yeasts, morels, and truffles.

- Basidiospores: These are sexual spores produced on the outside of a club-shaped structure called a basidium. Typically, four basidiospores are attached to a basidium by sterigmata. This type is characteristic of basidiomycetes, which include most familiar mushrooms.

- Zygospores: These are thick-walled resting spores formed during sexual reproduction in zygomycetes. They are highly resistant to unfavorable conditions and can remain dormant for extended periods before germinating.

Spore Dispersal Mechanisms

The successful propagation of fungi relies heavily on effective spore dispersal mechanisms, which allow them to spread to new, suitable habitats. Fungi have evolved a remarkable array of strategies to achieve this, often exploiting environmental forces or utilizing specialized structures.The primary methods by which fungal spores are dispersed include:

- Wind Dispersal: This is the most common and widespread mechanism. Fungal spores are often lightweight and produced in enormous numbers, making them easily carried by air currents over long distances. Many spores are adapted with specific surface textures or shapes that aid in aerodynamic lift and suspension.

- Water Dispersal: Spores can be transported by rainwater, streams, rivers, and even ocean currents. Aquatic fungi often produce spores with specialized structures, such as flagella, to facilitate movement in water. Splash dispersal, where raindrops dislodge spores from surfaces, is also significant.

- Insect and Animal Dispersal: Fungi have evolved symbiotic relationships with various insects and animals to facilitate spore dispersal. For example, some fungi produce attractive scents or nutritious structures that lure insects, which then carry the spores to new locations. Mycoheterotrophic plants also play a role in spore dispersal through their association with fungi.

- Self-Dispersal: Certain fungi have evolved active mechanisms for spore ejection. For instance, the force generated by the rapid drying of fungal tissues can launch spores away from the parent organism, a process observed in some puffballs.

Visual Descriptions of Spores Under Magnification

Under a microscope, fungal spores reveal a fascinating world of intricate shapes, sizes, and surface textures. These visual characteristics are often key diagnostic features used in mycology for species identification. The appearance can vary dramatically, from simple spheres to complex, elongated, or ornamented structures.When observed under magnification, spores can be described as follows:

- Shape: Spores can be spherical (globose), oval (ellipsoid), rod-shaped (bacilliform), needle-shaped (fusiform), or irregular. For example, the spores of Penicillium are typically globose to subglobose, while those of Fusarium are often crescent-shaped.

- Size: Spore dimensions are measured in micrometers (µm). They can range from just a few micrometers to hundreds of micrometers in length for some complex structures. For instance, many yeast spores are around 2-5 µm, whereas some large mushroom spores can exceed 15 µm.

- Color: Spores can be hyaline (clear or colorless), pigmented (e.g., brown, black, green, yellow), or even exhibit iridescent qualities. The color of a spore print, made by collecting spores shed onto a surface, is a critical identification feature for many mushroom species.

- Surface Texture: The outer surface of a spore can be smooth, warty (verrucose), spiny (echinulate), ridged (reticulate), or rough. For example, the spores of Agaricus species often have a smooth surface, while those of some boletes are distinctly reticulate.

- Cellularity: Spores can be aseptate (single-celled) or septate (divided by internal cross-walls called septa). Multicellular spores can have various arrangements of cells, such as chains or clusters.

Demystifying Spawn: The Living Fungal Culture

Fungal spawn serves as the vital starter culture for mushroom cultivation, essentially being the “seed” that introduces the mycelium to its growing medium. It is a pre-colonized material that contains a healthy and vigorous population of the desired mushroom species’ mycelium, ready to rapidly colonize the substrate and produce mushrooms. The primary purpose of spawn is to ensure a consistent and efficient transfer of living fungal tissue, thereby initiating and accelerating the fruiting process.Spawn is prepared by inoculating a sterile carrier material with a pure culture of mushroom mycelium, often derived from spores or tissue culture.

This inoculated material is then allowed to incubate under controlled conditions until the mycelium has thoroughly colonized the carrier. This colonization process is crucial for developing a robust and resilient spawn that can effectively compete with potential contaminants in the substrate.

Spawn Carrier Materials

The choice of spawn carrier material is critical as it provides nutrients and a physical structure for the mycelium to grow upon. Different materials are favored depending on the specific mushroom species, their nutritional requirements, and the overall cultivation strategy. The carrier must be able to absorb moisture, provide aeration, and be easily colonized by the mycelium.Commonly used spawn carrier materials include:

- Grains: Various grains such as rye, wheat, millet, sorghum, and corn are popular choices. They are rich in starches and proteins, offering excellent nutrition for mycelial growth. Grains are typically hydrated and sterilized or pasteurized before inoculation.

- Sawdust: Hardwood sawdust, particularly from species like oak, maple, and beech, is widely used for wood-loving mushrooms such as oyster and shiitake. It provides a good balance of carbon and some nitrogen. Sawdust often requires supplementation and careful moisture management.

- Legumes: Lentils and beans can also be used, offering a good nutritional profile.

- Straw: Chopped straw is a cost-effective and readily available substrate, particularly for species like straw mushrooms. It typically requires pasteurization to reduce competing microorganisms.

- Plaster of Paris (PoP) or Gypsum: While not a primary nutrient source, these materials are often added to other substrates like sawdust to improve aeration and moisture retention.

Spawn Preparation and Inoculation Stages

The preparation of spawn involves several key stages to ensure a clean, viable, and potent starter culture. These stages are designed to create an environment where the desired mushroom mycelium can thrive while preventing the growth of contaminants.The typical stages of spawn preparation and inoculation are:

- Substrate Preparation: The chosen carrier material is prepared. This usually involves cleaning, hydrating to an optimal moisture content, and then sterilizing or pasteurizing to eliminate competing microorganisms. Sterilization (e.g., using an autoclave) is more thorough and suitable for grain spawn, while pasteurization (e.g., heat treatment) is often used for materials like straw.

- Inoculation: Once the prepared substrate has cooled to a safe temperature, it is inoculated with a pure culture of the target mushroom species. This pure culture can be in the form of liquid culture (mycelium suspended in nutrient broth), agar wedges (mycelium growing on nutrient agar), or pre-made spawn from a trusted supplier. The inoculation process must be performed in a sterile environment to prevent contamination.

- Incubation: The inoculated substrate is then placed in incubation at the optimal temperature and humidity for the specific mushroom species. During this period, the mycelium grows and colonizes the carrier material. This can take anywhere from one to several weeks, depending on the species and the spawn’s volume.

- Colonization Check: As colonization progresses, the carrier material will become increasingly covered with white, fluffy mycelium. It is important to monitor for any signs of contamination, such as colored molds or bacterial growth. Fully colonized spawn will appear uniform with mycelium throughout the substrate.

Types of Spawn Based on Fungal Species

Different mushroom species have varying nutritional needs and growth habits, which influences the most effective types of spawn for their cultivation. The composition of the spawn, particularly the carrier material, is tailored to support the vigorous growth of the specific fungal species.Here’s a comparison of common spawn types based on fungal species:

| Fungal Species | Common Spawn Carrier | Characteristics of Spawn | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oyster Mushrooms (e.g., Pleurotus ostreatus) | Hardwood sawdust, straw, grain | Fast colonizing, vigorous mycelial growth. Sawdust spawn is common for bulk cultivation. | Tolerant of a wide range of substrates. |

| Shiitake Mushrooms (e.g., Lentinula edodes) | Hardwood sawdust, hardwood logs | Slower colonization than oysters, requires specific hardwood species for log cultivation. Sawdust spawn is often supplemented. | Requires a longer incubation period for full colonization. |

| Button Mushrooms (e.g., Agaricus bisporus) | Composted manure, straw, and grain (often a blend) | Requires a fully composted substrate for inoculation. Grain spawn is used to inoculate the compost. | Cultivated on a composted substrate rather than directly on spawn. |

| Lion’s Mane (e.g., Hericium erinaceus) | Hardwood sawdust | Dense, white mycelial growth. | Prefers well-hydrated sawdust. |

| Psilocybe cubensis (Magic Mushrooms) | Rye grain, millet, wild bird seed | Rapid and aggressive mycelial spread. Grain spawn is highly efficient. | Requires sterile conditions for optimal colonization. |

Defining Substrate: The Fungal Nutrient Medium

In the journey of mushroom cultivation, understanding the substrate is paramount. The substrate serves as the fundamental food source and the physical environment where the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, thrives and eventually fruits into mushrooms. It is essentially the “soil” for fungi, providing the necessary nutrients, moisture, and structure for growth.The concept of a substrate in fungal growth is analogous to the soil for plants.

Fungi are heterotrophic organisms, meaning they cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis. Instead, they absorb nutrients from their surroundings. The substrate is carefully selected and prepared to offer a rich blend of organic compounds that the specific mushroom species can efficiently break down and utilize for energy and growth. This process of decomposition is a key ecological role of fungi.

Common Types of Substrates Used for Mushroom Cultivation

The choice of substrate is highly dependent on the mushroom species being cultivated, as different fungi have evolved to thrive on specific types of organic matter. Selecting the right substrate ensures optimal colonization by the mycelium and ultimately leads to a successful harvest.Here are some of the most commonly used substrates in mushroom cultivation:

- Hardwood Sawdust: A very popular choice for many wood-loving species like Shiitake, Oyster, and Lion’s Mane. It is rich in cellulose and lignin, which these fungi can effectively decompose.

- Straw: Widely used for species such as Oyster mushrooms. It is readily available, inexpensive, and provides a good balance of carbon and nitrogen.

- Composted Manure: Often used in combination with other materials like straw or sawdust for species like Agaricus bisporus (button mushrooms) and Portobello mushrooms. The composting process reduces pathogens and stabilizes the nutrients.

- Grain: Primarily used as a spawn medium (as discussed previously), but can also be a component of some bulk substrates for specific species. Common grains include rye, wheat, millet, and corn.

- Coco Coir: A byproduct of the coconut industry, coco coir is excellent at retaining moisture and provides a good structure. It is often mixed with other ingredients like vermiculite and gypsum for various mushroom species.

- Wood Chips: Particularly useful for outdoor cultivation or for species that require a longer colonization period, such as Reishi and Maitake.

Examples of Substrate Preparation Methods

Preparing a substrate is a critical step that involves not only mixing the right ingredients but also sterilizing or pasteurizing it to eliminate competing microorganisms that could hinder mushroom growth. The goal is to create an environment that is favorable to the target mushroom species while unfavorable to contaminants.The preparation methods vary based on the substrate type and the cultivation method (e.g., indoor cultivation, outdoor logs).

Here are a few common approaches:

- Sterilization: This method involves heating the substrate to high temperatures (typically 121°C or 250°F) under pressure, usually in an autoclave or pressure cooker. This process kills virtually all microorganisms, making it ideal for grain spawn and some sawdust-based substrates. For example, hardwood sawdust mixed with a small percentage of bran and then sealed in autoclavable bags is sterilized for growing Shiitake mushrooms.

- Pasteurization: This involves heating the substrate to a lower temperature (around 60-80°C or 140-176°F) for a specific duration, typically using hot water or steam. Pasteurization kills most harmful bacteria and molds but leaves some beneficial microorganisms that can help protect the substrate from contamination. Straw is commonly pasteurized by soaking it in hot water or steeping it in a lime solution to achieve the desired temperature and pH.

- Composting: This is a biological process where organic materials are decomposed by microorganisms under controlled conditions. It is a more complex method often used for manure-based substrates. The material is piled and turned regularly, allowing for aeration and microbial activity to break down raw materials and stabilize nutrients.

- Supplementation: Many substrates are supplemented with materials like gypsum, bran, or calcium carbonate to adjust pH, improve water retention, and provide additional nutrients. For instance, a hardwood sawdust substrate for Oyster mushrooms might be supplemented with a small amount of gypsum to prevent clumping and improve water drainage.

Importance of Substrate Moisture Content and pH

The moisture content and pH of a substrate are two of the most crucial factors influencing fungal growth. Deviations from the optimal range for a specific mushroom species can lead to poor colonization, reduced yields, or complete crop failure.The ideal moisture content is essential for fungal metabolism and nutrient uptake. Mycelium needs water to transport nutrients and enzymes. However, too much moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions, promoting the growth of undesirable bacteria and molds, and can also hinder oxygen exchange.

The optimal moisture content for most mushroom substrates typically falls between 50% and 70%. This can be tested by squeezing a handful of the substrate; it should feel damp and a few drops of water should squeeze out, but it should not be dripping wet.

The pH of the substrate also plays a significant role in nutrient availability and the suppression of competing organisms. Different mushroom species have varying pH preferences.

Most cultivated mushrooms prefer a slightly acidic to neutral pH, generally ranging from 5.0 to 7.0. For example, Oyster mushrooms often thrive in a pH range of 5.5 to 6.5, while Agaricus bisporus prefers a slightly more alkaline environment around 7.0 to 7.5. Adjustments can be made using materials like lime (to increase pH) or sulfur (to decrease pH), depending on the specific requirements of the mushroom species.

Differentiating Spores, Spawn, and Substrate: A Comparative Approach

Understanding the distinct roles and characteristics of spores, spawn, and substrate is fundamental to successful mycology. While all are integral to the fungal lifecycle, they represent different stages, forms, and functions. This section will provide a clear comparison to help distinguish these crucial components.A direct comparison highlights how each element contributes uniquely to fungal growth and propagation. Spores are the starting point, spawn is the active growth engine, and substrate provides the sustenance.

Recognizing these differences is key to manipulating and optimizing fungal cultivation processes.

Comparative Functions of Spores, Spawn, and Substrate

The primary functions of spores, spawn, and substrate are fundamentally different, yet interconnected. Spores are designed for reproduction and widespread dispersal, ensuring the continuation of the species across diverse environments. Spawn, on the other hand, serves as a living inoculum, a concentrated source of actively growing mycelium ready to colonize new territory. The substrate’s role is purely nutritional and structural, providing the essential food and environment for the mycelium to thrive and develop.

Physical Differences Between Spores, Spawn, and Substrate

Visually and microscopically, these three components are easily distinguishable. Spores are microscopic, single-celled or multi-celled reproductive units, often appearing as dust-like particles to the naked eye. Spawn is a carrier material, such as grain, sawdust, or wood chips, that has been thoroughly permeated and colonized by the fungal mycelium, giving it a fluffy, white, or colored appearance depending on the species.

The substrate is the bulk material upon which the fungus grows, typically appearing as organic matter like composted manure, straw, wood logs, or even specialized nutrient mixes, varying greatly in texture and color.

Lifecycle Stage Representation

Each component represents a distinct phase in the fungal lifecycle. Spores are the initial, dormant stage, analogous to seeds in plants, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate. Upon germination, spores develop into mycelium, which, when introduced to a suitable carrier, becomes spawn. Spawn represents the actively vegetative and mobile stage of the fungus, poised for rapid expansion. The substrate is the environment that supports the vegetative growth of the mycelium originating from the spawn, leading eventually to fruiting body formation.

Comparative Attributes of Spores, Spawn, and Substrate

To further clarify the distinctions, the following table Artikels key attributes:

| Attribute | Spores | Spawn | Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Reproduction & Dispersal | Inoculum & Colonization Starter | Nutrient Source & Growth Medium |

| Physical Form | Microscopic reproductive units | Colonized carrier material (e.g., grain, sawdust) | Organic matter (e.g., wood, compost, straw) |

| Biological State | Dormant or active reproductive cells | Actively growing mycelium | Nutrient-rich, often pasteurized or sterilized |

| Size | Microscopic (typically 2-20 micrometers) | Visible, ranging from small grains to large bags of colonized material | Macroscopic, bulk material |

| Origin | Produced by mature fruiting bodies | Created by inoculating a sterile carrier with spores or mycelium | Prepared organic matter, often processed to reduce competing organisms |

Practical Applications in Fungal Cultivation

Understanding the distinct roles of spores, spawn, and substrate is paramount for successful fungal cultivation. These components form the foundational stages and ongoing processes of growing mushrooms, each contributing uniquely to the development of a healthy and productive fungal culture. Mastering their sequential use and proper preparation is key to achieving desired yields and species-specific outcomes.The journey of cultivating fungi is a testament to the intricate life cycles of these organisms.

From the microscopic beginnings of spores to the robust colonization of spawn and the nutrient-rich environment of the substrate, each element plays a critical, interconnected role. This section delves into how these components are practically applied in a typical cultivation workflow, highlighting the critical considerations for each stage.

Sequential Use in Cultivation

The cultivation of mushrooms follows a logical progression, beginning with the genetic material and culminating in fruiting bodies. This process is a carefully orchestrated sequence where spores initiate the cycle, spawn propagates the mycelium, and the substrate provides the necessary resources for growth and reproduction.The typical cultivation process begins with spores, which are the reproductive units of fungi, analogous to seeds in plants.

However, directly germinating spores into a substrate for large-scale cultivation can be slow and prone to contamination. Therefore, spores are often used to create a pure liquid culture or agar culture first, from which a viable mycelial culture is established. This established mycelium is then used to inoculate a grain mixture, creating what is known as spawn. Spawn is essentially a carrier material (like sterilized grain) fully colonized by the mycelium of a specific mushroom species.

This spawn then serves as the “starter” to inoculate a larger volume of a prepared substrate, which is the nutrient-rich material upon which the mushrooms will ultimately grow and fruit.

Role of Each Component in Mycelial Colonization

Each component plays a vital and distinct role in the overall success of mycelial colonization, from initiation to full saturation.

- Spores: These are the genetic starting point. When conditions are favorable, spores germinate into hyphae, which are the basic thread-like structures of a fungus. In cultivation, spores are primarily used in laboratory settings to establish new, pure cultures, often on agar plates.

- Spawn: Spawn acts as the living, active mycelial culture. It is a high-energy, fully colonized material that effectively introduces a robust population of healthy mycelium into the bulk substrate. This significantly speeds up the colonization process and reduces the risk of contamination compared to starting directly from spores.

- Substrate: The substrate is the food source and the physical medium for the mycelium to grow through and eventually fruit from. Its composition, moisture content, and sterilization level are critical for supporting healthy mycelial expansion and preventing the growth of competing microorganisms.

Considerations for Selecting Spawn and Substrate

The choice of spawn and substrate is highly species-dependent and requires careful consideration to optimize growth and yield. Different mushroom species have evolved to thrive on specific nutrient profiles and environmental conditions.For instance, wood-loving species like Shiitake ( Lentinula edodes) and Oyster mushrooms ( Pleurotus spp.) perform exceptionally well on substrates rich in lignocellulose, such as hardwood sawdust, wood chips, or straw.

They are often initiated with spawn grown on sterilized hardwood sawdust or rye grain. Conversely, species like Button mushrooms ( Agaricus bisporus) prefer composted organic matter, typically a blend of straw, manure, and other amendments, and are cultivated using specialized compost spawn. It is crucial to research the specific requirements of the target mushroom species. Factors such as the spawn’s carrier material (e.g., rye, millet, sawdust) and the substrate’s particle size, moisture content, and nutrient composition must align with the species’ natural habitat and dietary needs.

Step-by-Step Guide for Initiating Cultivation

Initiating fungal cultivation involves a series of precise steps, each designed to foster healthy mycelial growth and minimize contamination risks. This guide Artikels the fundamental process, starting from spores and progressing to a fully colonized substrate ready for fruiting.

- Starting with Spores: While not always the initial step in home cultivation, spores are the ultimate origin. They are typically introduced into a sterile laboratory environment, often via a spore syringe containing sterilized water and spores, or by streaking spores onto an agar plate. The spores germinate into microscopic hyphae, which are then cultivated on agar or in liquid culture to produce a pure, viable mycelial culture.

This pure culture is then used to create grain spawn.

- Preparing and Inoculating Spawn: Sterilized grain (such as rye, wheat, or millet) is prepared in jars or bags. Once the grain is cooled, a small amount of the pure mycelial culture (from agar or liquid culture) is introduced. This inoculation is performed under strict sterile conditions to prevent contamination. The inoculated grain is then incubated at an optimal temperature for the specific mushroom species, allowing the mycelium to grow and fully colonize the grain.

This fully colonized grain is the spawn.

- Preparing and Inoculating the Substrate with Spawn: The bulk substrate, chosen based on the mushroom species (e.g., sawdust and bran for many wood-lovers, or compost for button mushrooms), is prepared. This preparation often involves pasteurization or sterilization to eliminate competing organisms. Once the substrate has cooled to an appropriate temperature, the prepared spawn is introduced. This is typically done by breaking up the colonized grain spawn and mixing it thoroughly with the substrate, ensuring even distribution of the mycelium.

The ratio of spawn to substrate is important, with higher ratios generally leading to faster colonization.

- Monitoring Colonization: After inoculation, the spawn-substrate mixture is placed in a suitable environment for colonization, often in a dark, temperature-controlled area. The progress of mycelial growth is observed. Healthy colonization is indicated by the white, thread-like mycelium spreading throughout the substrate. The time it takes for full colonization varies depending on the species, temperature, and spawn rate, but it is a critical period where the mycelium establishes a strong network, preparing for the next stage of fruiting.

Contamination will appear as colored molds or bacterial growth, distinct from the white mycelium.

Visualizing the Differences

Understanding the distinct visual characteristics of spores, spawn, and substrate is crucial for successful fungal cultivation. This section will employ descriptive analogies and vivid imagery to help you differentiate these components at various stages, alongside guidance on visually assessing the health and progress of your fungal cultures.To truly grasp the distinctions, let’s explore some helpful analogies and detailed visual descriptions.

These will serve as a mental checklist as you observe your cultivation projects.

Analogies for Differentiation

Analogies can be powerful tools for simplifying complex concepts. By relating spores, spawn, and substrate to familiar objects or processes, their roles and appearances become more intuitive.

- Spores: Imagine spores as the microscopic seeds of a plant. They are incredibly tiny, often invisible to the naked eye, and represent the starting point of a new fungal life cycle. Like a single grain of sand on a vast beach, a spore is a minuscule entity with immense potential.

- Spawn: Think of spawn as a starter culture, akin to yeast for bread-making or a starter for sourdough. It’s a living, growing mass of mycelium that has been cultivated on a nutrient-rich medium (often grain or sawdust). Spawn is the actively growing, transplantable form of the fungus, ready to colonize a larger environment. It’s like a small, healthy seedling ready to be planted in a garden.

- Substrate: The substrate is the food source or the “soil” for the fungus. It can be composed of various organic materials like wood chips, straw, compost, or even specialized nutrient mixes. The substrate is what the mycelium will break down and absorb nutrients from to grow and eventually produce mushrooms. It is the fertile ground upon which the fungal organism will flourish.

Visual Appearance at Different Stages

The visual appearance of each component evolves significantly throughout the cultivation process, offering clear indicators of its status.

Spores

At their most fundamental, spores are microscopic. When viewed under a microscope, they can vary greatly in shape, size, and color depending on the fungal species. Some might appear spherical, others oval, and some even have intricate textures. When present in large numbers, such as in a spore print, they can form a powdery deposit, often white, brown, or black, on a surface.

Spawn

Spawn undergoes a dramatic visual transformation. Initially, it might resemble its carrier material (e.g., grains of rice or sawdust). However, as the mycelium begins to grow, it will start to envelop these particles.

- Early Stage: You’ll observe fine, white, thread-like structures (hyphae) emerging from the grains or sawdust. This is the initial colonization.

- Mid Stage: The white mycelium will become denser, forming a fuzzy or cottony blanket that covers the carrier material. The individual grains or particles may become less distinct as they are bound together by the mycelial network.

- Fully Colonized Spawn: The entire mass will appear as a solid, white, or sometimes off-white block or clump, with a firm, cohesive structure. The original carrier material will be almost entirely obscured by the dense mycelium. In some species, slight discoloration or the appearance of primordia (tiny mushroom beginnings) might be visible in fully colonized spawn.

Substrate

The substrate’s visual journey is equally dynamic, reflecting the colonization by the mycelium from the spawn.

- Uncolonized Substrate: This will simply look like the raw materials used. For example, straw will appear as golden strands, wood chips will look like woody fragments, and compost will have its characteristic dark, crumbly texture.

- Early Colonization: Patches of white, fluffy mycelium will begin to appear on the surface of the substrate, often originating from where the spawn was introduced. These patches will gradually expand.

- Partial Colonization: More of the substrate will be covered by white mycelium, but pockets of the original material will still be visible. The structure may start to feel more cohesive as the mycelium binds the substrate particles together.

- Full Colonization: The entire substrate mass will be enveloped in a dense network of white mycelium, similar to fully colonized spawn but on a larger scale. The original substrate material will be largely hidden. At this stage, the substrate may appear more compacted and sometimes slightly discolored.

- Fruiting Conditions: Once the substrate is fully colonized and exposed to the right environmental cues (temperature, humidity, light), you will observe the formation of pins (very small mushrooms) emerging from the mycelial network. These pins will then develop into mature mushrooms.

Visual Inspection for Successful Colonization

Effective visual inspection is your primary tool for assessing the health and progress of your fungal cultivation. It allows you to identify successful colonization, detect contamination, and determine when to move to the next stage.

Assessing Spawn Colonization

When inspecting spawn, look for consistent, healthy-looking white mycelial growth.

- Positive Indicators: A uniform, dense white covering over the entire carrier material is the ideal sign of successful colonization. The spawn should feel firm and cohesive, not loose or crumbly. A pleasant, earthy aroma is also a good sign.

- Signs of Contamination: Be vigilant for any colors other than white, such as green, blue, black, pink, or orange molds. These are often indicators of competing microorganisms that have outcompeted the desired fungus. Slimy patches or foul odors are also warning signs. If contamination is present, it’s usually best to discard the affected spawn to prevent it from spreading.

Assessing Substrate Colonization

The visual cues for substrate colonization are similar to spawn, but the scale is larger, and the substrate material itself is a factor.

- Positive Indicators: A consistent white mycelial network covering the surface and penetrating the substrate indicates successful colonization. The substrate should begin to hold together, showing increased structural integrity. A mild, earthy smell is expected.

- Signs of Contamination: As with spawn, any unusual colors (greens, blues, blacks, etc.), slimy textures, or foul odors on the substrate are strong indicators of contamination. Early detection is key, as contamination can spread rapidly through the substrate.

- Determining Readiness for Fruiting: A fully colonized substrate, appearing predominantly white and firm, is typically ready to be introduced to fruiting conditions. The extent of visible surface colonization is a good gauge, but internal colonization is also crucial. A slight “hardening” or “matting” of the surface can also suggest readiness.

By carefully observing these visual cues, you can confidently manage your fungal cultivation projects, ensuring healthy growth and maximizing your chances of a successful harvest.

Epilogue

In summary, distinguishing between spores, spawn, and substrate is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for effective fungal cultivation. Spores are the microscopic architects of reproduction, spawn acts as the living, colonized starter culture, and substrate provides the vital nutrient-rich environment for growth. Mastering these distinctions will empower you to initiate and manage your cultivation projects with greater precision and a higher likelihood of success, transforming theoretical knowledge into tangible, bountiful results.